PADDLEWHEELERS ON THE ST JOHNS

c.2005

by

Virginia M. Cowart

SUMMARY

When we think of paddlewheel steamboats, most of us picture the great Mississippi River boats. Mark Twain formed the mental picture most of us envision. Or we think of "Fulton's Folly" churning the waters of the Hudson.

But the paddlewheelers played a major part in the economic development of Jacksonville.

"Prior to the opening of railroads along the banks of the St. Johns a fleet of approximately 150 steamers carried freight and passengers on the river and its tributaries. These vessels made daily trips and during the peak period carried nearly 100,000 tons of freight each week. The aggregate of these vessels amounted to about $5,000,000. The U.S. Census of 1880 recorded that there was a larger fleet of steam vessels carrying passengers and freight on the St. Johns than on any river south of the Hudson in New York".(01)

Jacksonville's steamboats earned renown.

"Nearly all of the St. Johns River boats became famous locally in one way or another; some had a wider sphere of celebrity, and a few were known throughout the United States".(02)

The sidewheeler City of Jacksonville.

The story of St. Johns River paddlewheelers is a story of adventure in an area of the transportation business involving hazard, fantastic profit -- and intense competition.

"Competing steamer lines vied for business. companies extolled their own boats as floating palaces sporting Italian musicians or steam calliopes that tooted Where, Oh Where, Has My Little Dog Gone? Rival companies hinted that a competitor's boats were inferior and dangerous and that the bunks in their staterooms were "about the dimensions of a poor-house coffin".(03)

This paper examines the impact of early steamboats on the St Johns River by looking at parallels between the life story of one successful riverboat captain and the overall history of the business.

Captain Jacob Brock initiated the first regularly scheduled runs between Jacksonville and Enterprise ushering in the golden age of St. Johns River steamboats.

His story is their story.

"How do you get to Enterprise, Florida?" asks a voice from the back of the room.

You reply, "Why that's easy -- from Jacksonville, just take Interstate 95 south to Interstate 4 west, follow that until you get to exit 53. That will take you to Enterprise".

"But what if there were no Interstate 95?" asks the voice from the back.

"You could follow U.S. 17 south."

"But what if there were no U.S. 17? What if there were no roads at all?"

There was a time when there was only one "highway" -- a dirt track for ox carts, really -- anywhere on Florida's east coast.

Florida's first and oldest road was the King's Road which dates back to the British occupation of 1763 to 1783. It started in New Smyrna and ran north to Charleston, S.C. following essentially the same route as present-day U.S. 1.(04)

Florida's first and oldest road was the King's Road which dates back to the British occupation of 1763 to 1783. It started in New Smyrna and ran north to Charleston, S.C. following essentially the same route as present-day U.S. 1.(04)

So, how did people get around in those early days? How did plantations get outside supplies? How did farmers ship their produce to market?

Before there were other roads, early pioneers in Florida settled near the major waterways; those waterways were the roads of the day and riverboats carried virtually all freight and passengers. "For many years this broad river (the St. Johns) acted as a water highway over which came settlers, tourists, freight, and mail. The only other means of travel... was by ox cart or horse drawn vehicles, over long winding sand trails through the swamps and woods".(05)

In 1807 Robert Fulton successfully inserted a steam engine into a boat, the Clermont, to drive huge paddlewheels on either side of the boat.

"Fulton's Folly", as detractors called the project, changed the world.

"The steamboat was the first American invention of world significance. It was the first scientific accomplishment that gave man motion beyond the scope of the beast of burden or willful winds".(06)

The steamboat ruled America in transportation till the development of reliable railroads.

"The nemesis of the steamboat was hatched at about the same time as the craft that it would later, in large part, make obsolete. Seven years after Robert Fulton built the first practical steamboat, an Englishman, George Stephenson, built the first practical locomotive".(07)

But the paddlewheelers came first and they played a major part in the economic development of Florida.

The first steamer to ply the waters of the St. Johns River and the first steamer in Florida was the George Washington which started running in 1830.(08)

By 1834, the steamer Florida established regular service between Savannah and Picolata. In the Seminole Wars of the 1840s the Essayon carried troops and supplies along the river not only because of the convenience but also because the danger of overland travelers being ambushed by Indians.(09)

A typical riverboat of the 1840s, such as the Sarah Spaulding, accommodated passengers in eight berths, four on each side, opening into the saloon, but provided with curtains for privacy..(10)

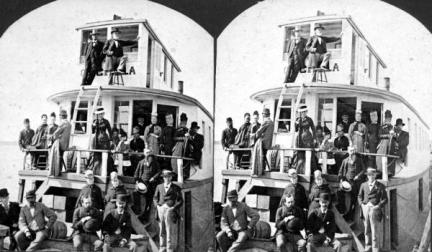

Steamboats on the St. Johns were generally of the coastal or river type since the same vessel was often used in both kinds of service. These "Eastern" type steamboats were often sidewheelers with one or two decks, fairly luxurious passenger accommodations, freight capacity, a single tall smoke stack, and steam engines located aft of amidships. Most St. Johns River steamboats were less than 200 feet in length and less than 30 feet wide (not counting the extra width over the paddle housings of sidewheelers). They are described as "most often having a shapely and graceful appearance.”(11)

By the end of the Civil War, Jacksonville had developed three primary industries: lumbering, tourism and exporting produce, especially oranges; although there was some overlapping, each type of industry normally called for its own type of ship. Thus, three main types of commercial vessels plied the St. Johns: the schooner, the side-wheeler and the stern-wheeler. Schooners were sailing ships with a fore and aft rig, i.e. the masts and sails were in a line down the length of the vessel; they were especially good at carrying bulky cargo. Side-wheelers were steamers with two paddle wheels located on each side admidships; they were usually employed as ocean-going vessels for both passengers and cargo. Most tourists arrived in Jacksonville from the north aboard side-wheelers. Stern-wheelers were steamers driven by one huge paddlewheel pushing the vessel from the rear; these shallow-draft vessels were good to maneuver in the relatively calm waters of inland rivers to bring produce from inland farms to the port.

"Lumbering relied upon the schooner; the other two were served by the steamboat, both the shallow-water and the oceangoing types. Naturally the shallow-water, or coastal steamer, held sway until the channel at the bar of the St. Johns had been deepened; then the ocean going steamers entered the port".(12)

While the last half of the 19th Century may have been the height of the Steamboat Era, the industry lasted well into the 20th Century and some elderly Floridians still remember seeing a river boat in their childhood. William Maierfeldt of Orange Park recorded a few such memories:

"You should not be surprised when getting aboard," he wrote, "To see a 12 foot alligator tired down on a 12 foot board" lashed to the deck. Oskey's, a store which catered to tourists wanting souvenirs of Florida, bought gators to transform them into handbags, shoes, belts, or suitcases.

Cargo overflowed the lower deck

Other deck cargo included wicker baskets of bread from the Rosenbush Bakery in Green Cove Springs, crates of live chickens (which sold for 50¢ each while eggs sold for 10¢ a dozen) tied-up pigs, and even hobbled horses or cattle.

Other deck cargo included wicker baskets of bread from the Rosenbush Bakery in Green Cove Springs, crates of live chickens (which sold for 50¢ each while eggs sold for 10¢ a dozen) tied-up pigs, and even hobbled horses or cattle.

Of the live cattle transported aboard the river boats, Maierfeldt said, "In most cases they were more wild than tame and it was some kind of problem to drive them onto the dock and into the steamer, and you can rest assured there were no passengers on the lower deck for the rest of the voyage... I can recall some of them had brass knobs on the ends of their horns to keep from running their horns thru a person -- not that the knob did much to lesson(sic) the danger".(13)

These cows sold for $18 per head.

"Milk was sold to the customer for 5¢ a quart, being ladled direct from a 5-gallon container by dipper."(14)

"I do recall catfish brought two and a half cents per pound on the hoof. If the fisherman skinned the fish he got a few cents more per pound".(15)

"These prices would seem ridiculous by today's comparison, but money in those days was real money and a man with one dollar in his pocket was considered a long way from being a pauper".(16)

All these details that Maierfeldt remembered came toward the end of the Steamboat Era, but how did this fascinating facet of the transportation industry get started on the St. Johns in the first place?

All these details that Maierfeldt remembered came toward the end of the Steamboat Era, but how did this fascinating facet of the transportation industry get started on the St. Johns in the first place?

Captain Jacob Brock was largely responsible.

In the fall of 1853, Captain Brock brought something new to the Florida territory -- regularly scheduled steamboat trips up the St. Johns River.

Capt. Jacob Brock

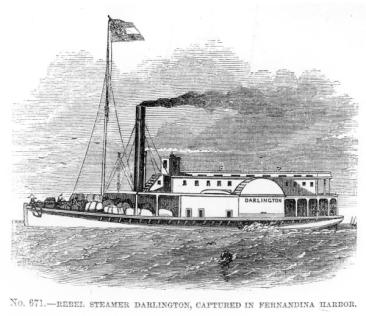

"Jacob Brock, a Vermonter, was among the early steamboat captains on the St. Johns. He recognized the tourist trade's potential. He was the owner of the Darlington, a western river-type vessel whose main deck was cluttered with freight surrounding the ship's engine. The Darlington was a South Carolina-built vessel completed in 1849. She spent her first years on the Pedee River traveling into the Darlington District, whence she got her name. Brock acquired her in 1852 to use between Jacksonville and his Brock House at Enterprise. Brock set aside a small salon for women and children to protect them from the vulgarity of the Grand Salon, although the latter served as the dining room at mealtimes".(17)

One of his passengers described him saying:

Captain Brock was a rough spoken man, but a kinder-hearted one or more congenial man never walked a deck or told a story. His boat had a most powerful and harsh whistle, that he blew by hitting a lever with a stick, and it was one of his most enjoyable jokes to get his passengers huddled round it, all absorbed in one of his stories and surreptiously hit the lever with his stick and blow the whistle to see the crowd jump and the women scream... Even among steamboat captains (Brock had) a notable reputation for the lavish and original nature of his profanity".(18)

After a time working in South Carolina, Captain Brock came to Florida. His wife, Jane, remained in Hartford, Connecticut, but his four young children, Jacob Jr., Charles, Hattie and Jennie came to Florida with him.(19)

He built a business transporting tourists and hunters up river aboard one of his several steamboats.

"The Brock Line of steamboats helped to open the St. Johns River area and make it accessible to the ever-increasing number of visitors and settlers coming to Florida. Never more than a few vessels, the line was important because it initially offered consistent service at a period when only a handful of steamboats were in the area".(20)

Riverboating was a difficult business.

"On Florida's rivers sidewheelers would not do; only stern-wheelers could hope to push their way through the masses of floating water hyacinths that clogged the streams. Here the crew had to be alert to slay for snakes that slithered from the Spanish moss on the overhanging trees to the deck of the boat and to shoot alligators before they tangled with the paddle wheel. When that happened usually neither the saurian nor the wheel survived the encounter".(21)

"On Florida's rivers sidewheelers would not do; only stern-wheelers could hope to push their way through the masses of floating water hyacinths that clogged the streams. Here the crew had to be alert to slay for snakes that slithered from the Spanish moss on the overhanging trees to the deck of the boat and to shoot alligators before they tangled with the paddle wheel. When that happened usually neither the saurian nor the wheel survived the encounter".(21)

In spite of thick water weeds, snakes and gators, Captain Brock saw a future for steamboating in Florida. He envisioned taking tourists and goods to the interior and bringing produce out.

In 1854, Brock ran the Darlington between Jacksonville and Palatka initially, but soon expanded service to Enterprise, where the water became too shallow for further navigation.

"Brock's first trip to Enterprise was with only one passenger and the return cargo consisted of one cowhide! By the advent of the Civil War, however, Brock's pioneering efforts had paid off and he was a wealthy man, owning considerable property and eleven slaves".(22)

How could he make a fortune after a start of transporting that first meager cargo?

"Early accounts of the steamboats give the impression that the passengers were largely lushs-- the bar was the most popular place on the ship". Whiskey sold for as much as 20¢ a drink ... "A steamboat operator could almost break even on the proceeds of the bar and dining saloon, even at 50¢ for a five-course dinner... Boats that carried two to three hundred passengers could make 100 per cent profit at the normal fare of $1.50. Annual profits of 70 per cent were not unusual, and one line paid a dividend of 6 per cent a month".(23)

"Early accounts of the steamboats give the impression that the passengers were largely lushs-- the bar was the most popular place on the ship". Whiskey sold for as much as 20¢ a drink ... "A steamboat operator could almost break even on the proceeds of the bar and dining saloon, even at 50¢ for a five-course dinner... Boats that carried two to three hundred passengers could make 100 per cent profit at the normal fare of $1.50. Annual profits of 70 per cent were not unusual, and one line paid a dividend of 6 per cent a month".(23)

Brock's first steamer, The Darlington, could carry 40 passengers. She had two decks, the lower for machinery and cargo, the upper for passenger cabins and two salons. In 1855, the Darlington's schedule called for her to leave Jacksonville at 8 a.m. Saturdays; arrive to spend Sunday in Palatka; Leave Palatka at 5 a.m. Monday and arrive in Enterprise that evening. She began her return trip at 5 a.m. Tuesday and arrived back in Jacksonville Wednesday afternoon. "It should be noted that the upper river was extremely crooked and narrow and was preferably run by daylight by the prudent captain".(24)

This schedule was arranged to dovetail with the schedule of ocean-going steamers so tourists freshly-arrived in Jacksonville could transship and continue their journey immediately.(25)

This schedule was arranged to dovetail with the schedule of ocean-going steamers so tourists freshly-arrived in Jacksonville could transship and continue their journey immediately.(25)

Brock House

In October, 1855, the captain opened his own hotel, Brock House, in Enterprise. A newspaper of the day describes it: "A large and commodious hotel which has been in the course of erection for some time.. is nearly complete and will be open early the coming winter". Hazen Peavey, a northerner who had managed Jacksonville's Judson House, managed the new hotel "with cooks and waiters from the north for the purpose of fitting up the house for the reception of guests".(26)A well-known character at Brock House was "Admiral Rose", the hostess known as "A legendary figure in the folklore of the region who ruled supreme. Her sharp commands were heard above the din and confusion at every landing. A woman of stout build and piercing eyes, she spoke the final word in her every tone and gesture".(27)

Brock House prospered.

One guest wrote:

From Jacksonville to Enterprise no hotel equals this. It is a genuine Northern-looking hotel, such as you may see at a watering place on the seaboard. It stands broadside to the lake, 110 feet long and two stories and a half in height, with a veranda its entire front, broad and airy. The house is well painted and has attractive green blinds, and comfortable accommodations for upward of 50 guests...

It was often filled to overflowing during the winter season...So great was the gathering of sportsmen that at times it was necessary to requisition some old boats as sleeping quarters for some of the guests and a mattress on a pool table was a real luxury.(28)

What attraction made guests willing to sleep on a pool table and think it luxury?

An anonymous correspondent, a yankee known only by the initials L.N. who was vacationing in Enterprise in the cold February of 1853, wrote to the New York Daily Times, gloating to the folks frozen back home:

I write you from the Southern extremity of steam navigation on the St. John's river. We have taken a long journey from its mouth to get here, about 300 miles, but are already richly repaid for our trouble.

How little can you imagine, sitting by your warm fireside, listening to the howling blasts of the month that often with you "comes in like a lion," as they roar about your doors and windows, of the beautiful out-door life we lead here, of the soft airs, and sweet perfumes that greet us at every step of our journey...

Every Northerner is agreeably surprised in the river. In size, it is grand and majestic and it sweeps along through the land with a sort of consciousness of its own strength...

In the Spring it is certainly one of the loveliest spots nature ever made.(29)

L.N. goes on to describe hanging festoons of Spanish moss draped from lofty branches, neat pretty cottages buried amid flowering foliage, winding paths of white sand through openings of soft green turf, fragrant flowering shrubs, a vine of yellow jasmine climbing over a tall tree and scattering its bright blossoms like stars on the ground, and the "delicate sensitive briar"!

"Did you ever imagine how delightful it is to go South and meet Spring, passing from the cold and frosty air of a northern latitude, the raw winds and the damp snowy sensation...?"

L.N. also describes the fun tourists can have shooting from the deck of a riverboat:

On the water we see ducks and geese, cranes and herons, snipes and fish-hawks... in such numbers the water was actually black with then; and like the hum of a vast multitude, the whole air was filled with their chatering noises... When a gun is fired into their midst, they rise like a cloud, but soon settle again on the water...

Many shots were fired (at alligators) from our boat and not a few of them took effect. One huge animal was killed with two shots from a double-barreled gun. he was at least 14 feet in length, and as the first shot wounded him he stood upon his legs, and opened his long jaws, when the second struck him in the head, and death transfixed him in this attitude. His mouth, throat, and tongue were of a light yellow and his large teeth were plainly to be seen. These teeth are much sought after by travelers and make very pretty ornaments when carved and polished.(30)

Around 1860, Captain Brock built his second boat, the Hattie Brock, named for his daughter. A contemporary account describes the vessel:

The Hattie Brock with schooners in the background

"The hole of the Hattie Brock can contain 800 bales of cotton. She has cabins to accommodate from 75 to 100 passengers, an excellent double engine, nearly new, and cost about $20,000. She was the best boat ever built expressly for the St. Johns trade"

The Hattie Brock was 131 feet in length, 25.3 feet wide, and a 5.4-foot deep cargo hole. The 217-ton vessel was a sidewheeler with two decks, "all in all rather crude in appearance with some sense of ruggedness".(31)

One passenger said of the Hattie Brock, "We were very comfortable on board of her. The table was good, the quarters clean, and the captain -- Charlie Brock -- a good fellow".(32)

Yes, indeed. Brock's business boomed. Things looked good commercially then...

Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861 -- cannon fire which began the Civil War. The very next day the steamer Cecile arrived in Jacksonville from Charleston with eyewitness accounts.(33)

Brock and his grown children, although transplanted northerners, served the Confederacy. Hattie married a Confederate officer; Charles served as a private in Captain James Kelly's Light Artillery, South Carolina Volunteers. Brock's wife, however, remained in the north nursing wounded Union soldiers.(34)

"With the outbreak of hostilities, many of the steamer captains plying the river turned immediately to blockade-running. Captain Jacob Brock had the distinction of bringing the first shipment into Jacksonville after the blockade had been proclaimed. He brought his Darlington loaded with provisions up to Cyrus Bisbee's wharf. Both men were New Englanders devoted to the Southern cause".(35)

About March 9, 1862, Captain Brock's Darlington was involved in one of the oddest naval gun battles of the Civil War:

Union troops commanded by Captain S.F. DuPont, chairman of the Blockade Strategy Board, arrived by ship in Fernandina just as Confederate troops were withdrawing from the city overland by train. The railroad tracks ran in a two-mile stretch immediately parallel to the Amelia River before crossing a railroad trestle.

DuPont dispatched the USS Ottawa, a shallow-draft gunboat, to blow up the trestle before the train could cross it. The gunboat and the train loaded with Confederate troops and civilian passengers raced for the bridge.

Where the rails ran close to the river, the gunboat opened fire on the train. Soon every window on the train bristled with rifle barrels as the Confederates returned fire spattering the deck of the Ottawa with hot lead.

A lucky shot from an Ottawa cannon burst in the last car of the train killing two passengers and disabling the car, which was loaded with furniture from the homes of fleeing civilians. Quickly the trainmen released the damaged car and abandoned it on the tracks.

Freed from the disabled car, the Confederate train raced across the bridge to safety.

To help with the evacuation of Fernandina, Captain Jacob Brock had packed every square inch of the Darlington with "military supplies, wagons, mules, forage and as many women and children as he could carry." As the Ottawa chased the train, Captain Brock raced the Darlington for the same bridge.

The vertical clearance for the bridge was so low that the large yankee gunboat could not pass; but Captain Brock had traveled through the channel often enough that he knew how to get his smaller steamer under the bridge.

Seeing both the Confederate train and the Darlington headed for escape trying to save the Confederate supplies and household goods, the Commander R. P. Rogers launched two armed smaller boats from the Ottawa in full pursuit of Captain Brock.

"Only when all means of escape had eluded him did Brock surrender. Afterwards, DuPont reported that 'the brutal captain (Brock) suffer her (the Darlington) to be fired upon and refused to hoist a white flag, notwithstanding the entreaties of the women. No one was injuried".(36)

The Union Army imprisoned Captain Brock at Fort Lafayette, New York, and later at Fort Warren, Boston. Near the end of the war he secured his release and returned to Florida by way of Nassau.(37)

"Brock was taken into custody and suffered much vilification... (He) was placed in jail despite his civilian status, for two offenses: his attempts to escape and his complete lack of northern sympathies despite his birthplace".(38)

The yankees requisitioned the captured Darlington into their own navy, giving her a crew of 25 and two 24-pound howitzers. She was used against the South from Florida to the Carolinas. "At the close of the war she was laid up in South Carolina waters, at Beaufort or Hilton Head".(39)

Two days after Confederate troops completed withdrawal from Fernandina, four Union gunboats steamed up the St. Johns to Jacksonville and trained their guns on the city; Sheriff Frederick Lueders tied a white flag to his walking cane and surrendered to keep the invaders from shelling the defenseless city.(40)

During the war, most steamboats on the river were Federal ones carrying troops on invasions.

"While the Confederates had had the advantage of land, the Union forces were better equipped for water transportation and took advantage of this by pushing up the St. Johns River and landing a force at Palatka. On March 13, the Columbine captured the Confederate steamer Sumter on Lake George with all its officers and crew. A few days later the Hattie Brock with one hundred and fifty bales of cotton, was captured by a Union gunboat. These were serious losses to the Confederacy for these small boats were of great value in navigating the river, where large boats could not operate".(41)

How did the Yankees use Brock's ship?

While he was a POW, during the second occupation of Jacksonville by Federal troops, "A convoy of gunboats escorted by the captured Confederate steamboat Darlington carrying a company of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, on a raid up the St. Johns River, the steamer Governor Milton, which had rendered such valuable service bringing General Finegan's guns to St. Johns bluff, was discovered in a creek near Enterprise and burned. The party also raided and burned plantations and farms for a distance of 200 miles along the St. Johns. It was an expedition typical of many that were to follow along the St. Johns and characterized the last years of the war in East Florida".(42)

Finally the war ended.

"River traffic, brought to a complete stand still during the war, picked up quickly. In a six-day period from July 9 through 13 (1864), four steamers and three schooners arrived in port (of Jacksonville) and by December of 1865 a new line reopened regularly-scheduled traffic between Charleston, Jacksonville and points south on the St. Johns River".(43)

Brock got both of his boats, Darlington and Hattie Brock, back.

Apparently, Brock had a loose partnership with another Confederate sympathizer from the north, John Clark, who acted as Brock's freight and passenger agent. In May of 1866, the Federal government sold the Hattie Brock to John Clark -- who immediately turned around and sold the ship back to Brock, its original owner.(44)

Captain Jacob Brock refitted his famous Darlington and resumed the run between Jacksonville and Enterprise in July of 1866.(45)

While prosperity was not immediate for any community right after the War, an indication of what was to come also appeared in 1866: Captain Brock's Darlington began running regular excursions from Jacksonville to Enterprise and Green Cove Springs was becoming widely known. "The water is drank (sic) exclusively by everybody in the vicinity and its efficacy for diseases of the skin and blood is unsurpassed," said one tourist. Soon other "steam yachts" were making the Green Cove Springs run in addition to the regular steamboats. By 1869 a New Yorker making the excursion noted that steamboat passengers consisted of four main classes: tourists and pleasure seekers, health seekers, residents -- and land speculators.(46)

Brock expanded his operations in several areas related to riverboating.

For instance, he entered a contract with the Freedmen's Bureau which had converted the Magnolia Hotel into a hospital and sent many patients up river aboard the Darlington.(47)

This may not have been a very profitable contract.

On March 26, 1866, Major Arthur Williams, who supervised the move of patients in the Freedmen's Bureau Hospital from Jacksonville to Magnolia, demanded of the hospital board that the hospital get its own river boat. He pointed out that roads were inadequate, too rough for the transportation of sick people by horse and wagon, and that ordering supplies by land was inefficient. The board was not willing to buy a boat but instead contracted with Captain Brock's Darlington for the service. But even then, the board would not pay transportation expenses for new incoming patients -- only for discharged ones!

Thrift bordering on stinginess characterized the hospital board; when a surgeon requested that hospital gowns be ordered from Jacksonville, the board insisted that he order bolts of cloth and either employ seamstresses or have female patients sew their own.

Even with such tactics, "It does not appear that the work of the Freedmen's Bureau caused resentment in Clay County even though the agency's presence caused hatred in may parts of the State".(48)

Brock also resumed his hotel business. But the war had hurt; yankee looters had stripped Brock's hotel to a ghost of its former self. A female guest in 1867 complained, "The Brock House... is filled with invalids mostly, consumptives who find this climate unrivaled for pulmonary disease, dry and hot..."

Another border gripped, "This house is quite primitive, no carpets, curtains nor luxuries, but when out doors is so charming you can wink at the discomforts inside... where passengers left the steamboat to make merry (in the hotel bar)..."

But Captain Brock's hotel eventually did regain its former status and popularity.

The guest list at Brock House came to include such notables as President Ulysses Grant, President Grover Cleveland, General William Sherman and William Jennings Bryan. Not only yankees but even foreigners from England, France and South Africa came to Brock House.

Brock’s shipyard

In Jacksonville, Captain Brock built a shipyard -- on the same site as the recently sold Jacksonville Shipyards Inc. Brock's yard formed a partnership with a carpetbagger northerner named Stevens to become the Brock Stevens Shipyard, which in turn eventually became the Merrill Stevens Shipyard.(49)

In Jacksonville, Captain Brock built a shipyard -- on the same site as the recently sold Jacksonville Shipyards Inc. Brock's yard formed a partnership with a carpetbagger northerner named Stevens to become the Brock Stevens Shipyard, which in turn eventually became the Merrill Stevens Shipyard.(49)

Brock also became the state agent for selling a new type of petroleum-derived lamp fuel designed to replace sperm whale oil. Kerosene lamps came to light many Florida homes.(50)

Brock also restored his freight business; cargo rates in 1868 were:

Cotton, per bail -- 25¢

Corn, per bushel -- 1¢

Flour, per barrel -- 12¢

Flour, per sack -- 5¢

Hay, per bail -- 12

Salt, per sack -- 12¢

Coffee, per sack -- 12¢

Whiskey, per barrel -- 12¢ (51)

But as Brock's business grew more competition entered the river.

In 1868, Frederick De Barry, a wealthy wine merchant of New York, bought an estate on Lake Monroe in Volutia County near Enterprise and established his winter residence there... (In 1876, he placed the George M. Budd in commission under Captain Amazeen(sic) and this started the De Barry Line, which was later combined with the Baya Line, under the name of De Barry-Baya Merchant Line, which comprised a fleet of thirteen steamers in 1885. The line ran from Jacksonville to all points on the St. Johns River, secured the mail contract and later established steamers on the "Sea Island Route" to Savannah".)(52)

The trip aboard Brock's Darlington from Jacksonville to Enterprise, a distance of 206 miles, took 36 hours; the fare in 1869 was nine dollars per person.(53)

Captain Brock's son, Charles, began working with his father in the steamship business. Soon the Brock Line added other vessels: the Robert Lehr, which only ran a short time; the refitted Darlington, which celebrated its return to its rightful owner by offering a free excursion to Green Cove Springs for 350 people. "Music and dancing were provided on board by the good captain".(54)

He did not lack customers; tourists flocked to north Florida.

What was the attraction for them?

"'No dreamland on earth can be more unearthly in its beauty and glory than the St. Johns in April,' Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote in 1873 when she returned from a grand round or tour of the river fin the vicinity of Jacksonville, Enterprise, and St. Augustine. With the sights and sounds of the St. Johns country still fresh in her mind, Miss. Stowe rhapsodized: 'Tourists for the most part, see it only in winter, when half its gorgeous forests stand bare of leaves, and go home, never dreaming what it would be like in its resurrection robes'".(55)

The profits the Brock Line earned attracted the attention of competitors; other riverboats appeared on the river: Starlight, City Point, Dictator and others. Brock responded to the competition by adding another vessel to his line, the Florence.

The profits the Brock Line earned attracted the attention of competitors; other riverboats appeared on the river: Starlight, City Point, Dictator and others. Brock responded to the competition by adding another vessel to his line, the Florence.

The Florence, built in Wilminton, Delaware, was 176 net and 263 gross tons. She measured 135 feet long and 24.4 feet wide with a cargo hole of 6.8 feet. Brock's son, Charles, captained the Florence. To finance the Florence Brock mortgaged the Brock House and 323 acres of land in Enterprise to the shipbuilders. And a few months later, he borrowed money, using the Darlington and the Hattie Brock as collateral, to buy out his northern partners.

By 1872 keen competition forced Brock to revise his Jacksonville fare rates for the Florence: 1$ to Green Cove Springs and $2 beyond.(56)

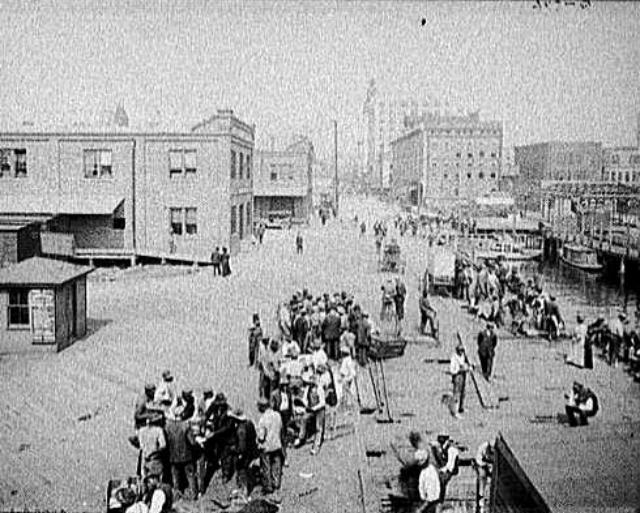

Jacksonville’s busy waterfront. Late 1800s

Competition increased even more as more and more entrepreneurs saw the profits to be made in the St. Johns riverboat business.

"The river teemed with craft which, according to a report of the County Commissioners published in 1885, numbered seventy-four vessels totaling 8,168 registered tonnage, with estimated value of river commerce of $2,042,000. This was claimed to have been the largest tonnage of any inland local traffic south of the Hudson River. The estimated value of vessels and cargoes arriving and departing from Jacksonville was $38,270,000 in 1882. Among the articles of commerce mentioned are 37,440 bales of cotton, 68,041,548 feet of lumber and 316,800 crates of fruit and vegetables. In 1885, Duval was sixth in the state in the production of oranges".(57)

Brock responded to his competitors by beginning to build his own schooner, planning to expand his operations by entering the lumber transport aspect of the business... but tourism remained the backbone of his efforts.

The riverboat tourist business was so good in Jacksonville that some companies transferred some of their luxury craft from the Mississippi-New Orleans run to the St. Johns. Typical of this type vessel was the Fannie Dugan, which drew only 32 inches of water. When finally refitted for the St. Johns (in 1882), she boasted of thirty staterooms, each with two bunks, around a 120-foot salon. Each stateroom had one door opening into the grand salon and one opening out onto a promenade deck.(58)

Brock placed even greater emphasis on his own excursion business.

What was a trip on one of Brock's riverboats like?

On May 7, 1874, parents, teachers and children from the Newnan Street Presbyterian Sabbath School took an excursion trip aboard the Florence:

At 9:00 punctually... many friends were assembled on the deck of the beautiful FLORENCE which through the kindness of Captain Brock having placed her at our command for the day... At the last sound of the whistle the swift-winged FLORENCE dashed from her wharf and soon a beautiful floral city lingered on the vision only as a dream. Billows, hamlets and groves passed by as things of life and they were soon lost to view on deck and cabin. Innocent merry hearts with song and shout were making melody such as angels might approve... Even the gallant purser caught the infection and proved by his fascinating devotion as deft in the use of honeyed words and bewitching glance as with cash and ledger...

Nor was the conclusion (of the trip) unworthy of the occasion... amid innocent mirth there was the old, young and gay and with many expressions of thanks to Captain Brock... with grateful acknowledgments to the Giver of all good, returned to our happy homes as contented a picnic party as ever had been on the advent of May.(59)

Not all trips went so well.

On the Fourth Of July that same year, the St. Johns Shooting Club "patriotically moved and socially inclined" rode the Florence to Mayport and a short way out into the ocean.

That was a mistake:

Dinner was announced and the hungry crowd sat down to the well spread table. Hardly through the first course and well on to the second course when the steamer struck the first heavy swell. All smiled languidly and looked brave and one ferocious member of the club who had traveled called vigorously for the coconut pie. It was no use, swells succeeded, lips grew white and even brave shooting men... had sudden business with the captain. After pitching and rolling for some few minutes and the rain coming down not hard but persistently, the south beach and surf bathing was abandoned and a return to Mayport voted.

But the day was not a total loss; on their return to Jacksonville, the passengers enjoyed watching fireworks over the city from the deck of the Florence.

From the center of the stream the display was rendered beautifully and too much praise could not be awarded... The program was one that would reflect credit on a much larger city than ours.(60)

Other riverboat lines vied for the excursion business.

About this time the Hattie Barker, Katie, Lollie Boy, Volusia, Daylight, and Starlight all joined in the race to Enterprise against Brock's fleet.(61)

Hattie & Starlight prepare to race

The Florence set a St. Johns River record by running round-trip between Jacksonville and Palatka in only 13 3/4 hours -- making all the landings along the way!(62)

Competition became "head-knocking" -- rival steamboats began to race on the St. Johns literally. And these races lead to collisions: Florence vs Dictator; David Clark vs Cracker Boy; Darlington vs Starlight -- the trial on that one brought forth 35 witness and produced over a thousand pages of evidence transcript!(63)

To tow damaged riverboats to his ship repair yard, Brock also added a tug, the R.L. Mabey, to his fleet.

The noble Darlington wore out in service. In March, 1874, her machinery stripped out for salvage, she was abandoned on a forgotten river mudflat. To replace her, Brock's shipyard began construction of a new boat, the David Clark. A Jacksonville Tri-Weekly Union newspaper report said the new boat "is something of a boat as the length of keel is 140 feet and... the salon will be 110 feet long. Forty full sized staterooms with all the modern improvements... and a spacious promenade is provided in the salon.. The wheels are 24 feet in diameter and 8 feet wide, making ample propelling power".(64)

Still dependent mostly on the excursion business, Brock began to offer special rates to groups as diverse as Episcopal Church Women, the -- wet -- Volunteer Fighters, and the --dry -- Sons Of Temperance. He also initiated special cruises for all-black groups.

He even tried consolidating with a rival line.

Yet, Brock vessels operated at a loss. He sold the Brock House in 1876, trying to keep his ships afloat.(65)

Also in 1876, perhaps foreseeing the future, Brock changed wharfs -- his fleet began docking in Jacksonville at a wharf where railroad trains discharged northern passengers who wished to connect with river boats headed further south.(66)

His vision of the future came too late.

In May of 1877 Captain Brock declared voluntary bankruptcy.

At public auction, the David Clark sold for $20,000; the Robert G. Reiman, a Brock tug, sold for $1,000; the under-construction schooner went for $5,000. But the queen of the fleet, the Florence, was purchased by Captain Brock's son, Charles, for $14,000 (Charles Brock continued to operated river boats on the St. Johns till 1904).

Captain Jacob Brock died on September 22, 1877, at the age of 66. His obituary said,

Captain Brock's name was a household word from one end of the river to the other, generous to a fault, rough in his ways and language, the poor and needy knew him best... he may be called the pioneer steamboat man of the St. Johns river and the business became a success under his management.(67)

An advertisement printed for a rival steamship line years later may have described Captain Brock's accomplishments better than his own obituary did:

Tis but a few years since the question of a tour of the splendid natural domain described in the foregoing pages, via the great highway of the peninsula, the broad and forested environed St. Johns river, presented so many obstacles that but comparatively few travelers had the courage to invade the vast reaches of territory tributary to and accessible by the river. Now it is the exceptional visitor to Jacksonville who fails to enjoy the round trip to Enterprise and return. In those days the boats running without definite schedule, stopping for vexatious hours at minor landings for freight -- their principal means of support; home-made steamers, small, cramped and hot, with fare suggestive of the primitive 'grub' of the mining camp, and beds about the dimensions of a poor-house coffin; such were the craft the travelers found upon the upper St. Johns river.

Now, things are as they should be; and the invalid, demanding not only easy and swift transportation, but even the luxuries supposed to exist only upon the northern rivers, will find that he can go to Enterprise and back with as little to complain about as he will meet with upon the great Sound lines between New York and Boston.(68)

Ten years after Brock's death, the St. Johns and Halifax Railroad reached Daytona. And the Jacksonville, Tampa & Key West Railroad soon reached Sanford where it connected with roads extending South and West.

"The coming of the railroad brought a rapid development throughout the County but it also slowed the traffic on the St. Johns... The coming of the railroads; the decline in the river traffic, the yellow fever epidemic of 1888 ... and the "Big Freeze" of 1894-5 has left Enterprise to sleep there on the shore of Lake Monroe".(69)

But what of the paddlewheelers? What happened to them?

"The fate of a large number of them was one of disaster and their remains lie scattered from the bar to the far upper reaches of the river and along the coast from Brunswick to New Smyrna... All left a history interwoven with romance -- the romance of the St. Johns River".(70)

Endnotes & Bibliography Follow

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at

ENDNOTES

01. James C. Craig, "Steamboating Days." In Papers Of The Jacksonville Historical Society Vol. III (1959), page 141.

02. Frederick T.Davis, History Of Jacksonville, Florida, And Vicinity, 1513 to 1924. (Jacksonville: San Marco Bookstore. Original copyright, 1925), p. 366.

03. John W. Cowart, "Paddlewheeler, passengers met disaster on St. Johns." in Florida Times-Union Nov. 8, 1982.

04. Ianthe Bond Hebel, Centennial History Of Volusia County, Florida 1854 - 1954, (Daytona Beach, Fla.: College Publishing Co. c. 1955), p. 13.

05. Hubel, Centennial History of Volusia County, p. 62

06. Frank Donovan, River Boats Of America, ( New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co. c. 1966), p. 12.

07. Donovan, page 13

08. Davis, p. 358.

09. Davis, p. 358.

10. Davis, p. 358 and Donovan p. 13.

11. Edward A. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, (Melbourne, Fla. Published by the Kellersberger Fund of the South Brevard Historical Society. c. 1980) p. 10

12. George E.Buker, Jacksonville: Riverport -- Seaport, (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. c. 1992) p. 73

13. William C. Maierfeldt, Early Days In Orange Park, ( 30 page self-published booklet; no copyright) pp. 5-6.

14. Maierfeldt, p. 24.

15. Maierfeldt, p. 18.

16. Maierfeldt, p. 16.

17. Buker, p. 46

18. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 59.

19. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 51.

20. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 51.

21. Donovan,, p. 64.

22. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 52.

23. Donovan, p. 69.

24. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 52.

25. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 54.

26. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 52.

27. Floyd and Marion Rinhart, Victorian Florida: America's Last Frontier, (Atlanta, Ga.: Peachtree Publishers Limited. c. 1986), p. 56.

28. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 53.

29. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 29 - 30.

30. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 30 - 31.

31. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 56.

32. Rinhart, p. 62.

33. Buker, p. 51.

34. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 54.

35. Buker, p. 52.

36. Buker, p. 55-56.

37. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 56.

38. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 55.

39. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 55.

40. James Robertson Ward, Old Hickory's Town, (Jacksonville, Fla.: Florida Publishing Co. c. 1982), p. 142.

41. Pleasant Daniel Gold, History Of Duval County, ( St. Augustine, Fla.: The Record Co. c. 1928), p. 145.

42. Richard A. Martin, The City Makers, (Jacksonville, Fla.: Convention Press Inc. c. 1972), p. 49.

43. Martin, p. 76.

44. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 56.

45. Martin, p. 270.

46. Arch Fredric Blakey, Parade Of Memories: A History Of Clay County, Florida, (Jacksonville, Fla.: Published for the Clay County Board of County Commissioners by Drummond Press. c. 1976), p. 125.

47. Buker, p. 73.

48. Blakey, pp. 115 - 117.

49. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 57.

50. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 59.

51. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 58.

52. Gold, p. 186.

53. Rinhart, p. 56.

54. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 57.

55. Martin, p. 108.

56. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 58.

57. Gold, p. 186-187.

58. Buker, p. 79.

59. Edward A. Mueller, St. Johns River Steamboats. (Jacksonville, Fla.: Privately published by Mendelson Press. c. 1986) p.112 - 113.

60. Mueller, St. Johns River Steamboats, p. 115.

61. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 61.

62. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 60.

63. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 58-60.

64. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 60.

65. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 61.

66. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 61.

67. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 62.

68. Mueller, Steamboating On The St. Johns, p. 81.

69. Hebel, p. 5.

70. Davis, p. 366.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blakey, Arch Fredric. Parade Of Memories: A History Of Clay County, Florida. Jacksonville, Fla.: Published for the Clay County Board of County Commissioners by Drummond Press. c. 1976. 311 pages. Index.

Buker, George E. Jacksonville: Riverport -- Seaport. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. c. 1992. 192 pages. Index.

Cowart, John W. "Paddlewheeler, passengers met disaster on St. Johns." Florida Times-Union Nov. 8, 1982.

Craig, James C. "Steamboating Days." In Papers Of The Jacksonville Historical Society Vol. III (1959), pages 138 -145.

Davis, T Frederick. History Of Jacksonville, Florida, And Vicinity, 1513 to 1924. 1990 Reprint. Jacksonville: San Marco Bookstore. Original copyright, 1925. 513 pages. Index.

Donovan, Frank. River Boats Of America. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co. c. 1966. 298 pages. Index.

Gold, Pleasant Daniel. History Of Duval County. St. Augustine, Fla.: The Record Co. c. 1928. 234 pages. Index.

Hebel, Ianthe Bond. Centennial History Of Volusia County, Florida 1854 - 1954. Daytona Beach, Fla.: College Publishing Co. c. 1955. 205 pages. Index.

Maierfeldt, William C. Early Days In Orange Park. 30 page self-published booklet; no copyright.

Martin, Richard A. The City Makers. Jacksonville, Fla.: Convention Press Inc. c. 1972. 334 pages. Index.

Mueller, Edward A. St. Johns River Steamboats. Jacksonville, Fla.: Privately published by Mendelson Press. c. 1986. 219 pages. No index.

Mueller, Edward A. Steamboating On The St. Johns. Melbourne, Fla. Published by the Kellersberger Fund of the South Brevard Historical Society. c. 1980. 124 pages. No index.

Rinhart, Floyd and Marion. Victorian Florida: America's Last Frontier. Atlanta, Ga.: Peachtree Publishers Limited. c. 1986.223 pages. Index.

Ward, James Robertson. Old Hickory's Town. Jacksonville, Fla.: Florida Publishing Co. c. 1982. 256 pages. Index.

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at