MARY AND THE BEAN STALK

c.2005

by

John W. Cowart

From the book People Whose Faith Got Them Into Trouble (IVP, 1990)

Mary Slessor

December 2, 1848 to January 13, 1915

Presbyterian missionary Mary Slessor held their bag of beans and would not give it back.

Scores of sullen, threatening African warriors faced the lone woman.

She had snatched the leather sack containing 40 beans right out of the chief's hand and refused to give it back to him.

The warriors surrounding her rattled ironwood spears against their rhinoceros hide shields. Some shook clubs in her face. Others swung broad flat-ended swords over her head. All screamed and shouted at her.

Still, she would not give them back their beans.

She marched through the mob of screaming drunken warriors to her mud hut, carried the sack of beans inside, shut the door and went to bed.

All night, the warriors milled around outside her door, drinking trade rum, cursing and wondering what to do about the bag of beans.

This encounter took place in 1890 near the mouth of the Calabar River in Calabar, Africa, a country on the west coast just north of the equator.

It was one of many confrontations between Mary Slessor and armed tribesmen over the beans. They also faced off in confrontation over twins, over women, over slavery, over intertribal warfare, over justice, Egbo, JuJu and the gospel of Jesus Christ.

" I am trembling for the meetings," she once wrote. "But surely God will help me. It is His own cause. I am suffering tortures of fear, and yet why is it that I cannot rest in Him? If He sends me work, surely He will help me deliver His message and do it for His glory. He never failed me before. If He be glorified that is all whether I be considered able or not."

The mental anguish she expresses on paper was not generated by a confrontation with wild bush men -- she wrote this about having to speak at a church meeting in her own home town in Scotland! Yes, Mary Slessor was a wee lassie so shy that she got stage fright and avoided speaking in public. When home she was afraid of cows. She even feared crossing the street by herself and had to be helped!

Yet God gave her a holy boldness for working in one of the most challenging mission fields on earth

On the African Slave Coast in those days, the land of Calabar, now known as Nigeria, took its name from the bean -- or vice versa. The geographic names reflected the area's two most notable features: slavery and the Calabar Bean.

The Africans of the Slave Coast continued to enslave each other long after Europe and the United States abolished slavery. Slave pens at the port were among the first things Mary Slessor noticed when she arrived in Calabar in 1876. Strong tribes captured weak ones and sold them to still other tribes or herded their captives northeast to meet Arab slavers. Slavery was still an active force in the local area until the British colonial government stopped it after World War I.

Use of the Calabar bean also shaped the area's culture.

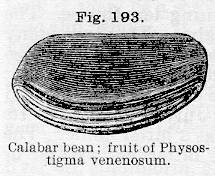

The brown bean, Physostigma venenosum, grows in pods about six inches long. Nothing in the bean's taste, smell or appearance distinguishes it from other beans. The difference is discovered after it is eaten.

First the bean's chemical increases the output of the victim's salivary glands. Then it constricts the blood vessels leading to those glands. The blood pressure rises. Violent vomiting begins. The actions of bladder, uterus, spleen, eyes, heart and lungs fluctuate wildly. Tremors and convulsions of the spinal cord set in.

Mental functions are not affected; the victim is completely conscious of what is happening to him during all of this. Finally, the poison bean causes the bronchial tubes to constrict while the secretion of the glands is stepped up. The lungs become waterlogged; death follows as the victim drowns in his own spit.

Feeding sacrificial victims the bean and watching the ensuing show was a major part of the region's religious heritage.

Four other elements characterized the religious animism of the area: fear of JuJu, evil spirits believed to reside in trees, rocks and animals; fear of witchcraft; fear of secret societies known as Egbo; and fear of dying alone.

These fears expressed themselves as cruelty.

For instance, the tribes believed that all sickness is evil and comes from the devil. Therefore, whenever a person got injured, fell sick or died, then obviously the trouble was the result of a witch siccing a demon on the sufferer. This crime called for a trial.

They tried accused people in two ways: oil and beans. In the oil trial boiling palm oil was poured on the naked belly of the person accused of the crime. If it scalded  him, he was guilty; if he survived, he must be innocent.

him, he was guilty; if he survived, he must be innocent.

The bean trial worked the same way.

The chief or witch doctor forced the accused victims to take the bean.

Innocent people did not go into convulsions and die; the guilty did.

Of course, only the witch doctor who picked the beans could tell which kind of bean plant a particular bean came from originally.

When a member of a chief's family became sick or was in an accident or was killed in war, dozens of suspected witches, male and female, were forced to take the bean test. These trials were an almost daily affair.

Another way the religious fears of the people came out in daily life was in their burial customs. When a man died, his wives and slaves had to accompany him into the spirit world. The more important the dead man, the higher the number of people strangled at his graveside to be buried with him.

A third expression of animism's fears was in the people's dread of twins. They believed that a human man could only begat one child at a time. Therefore, if a woman gave birth to twins, that meant she had been having intercourse with a demon.

Now, some genetic factor seemed to cause a great many twins to be born in this part of the world. The mothers were cast out of the tribe to die in the bush: the newborn babies were immediately stuffed into clay pots and left outside the village for ants to eat.

A living twin was thought to be a demon incarnate who could curse and bring disaster on the whole tribe. Mothers who gave birth to twins believed they had been raped in their sleep by a demon and immediately threw away the evidence. The gods, good taste and public well-being depended on these abominations being exterminated at birth.

Notice that just about all of these cruelties primarily involved women. Women -- even those who were not outright slaves -- were the property of their fathers or husbands. When a girl reached a marriageable age she was placed in seclusion and fattened to increase her bride price. Once married, she lived in a harem with her husband's other wives.

When the Egbo societies raided a village, the women were beaten and degraded in wild orgies. When a husband died, they were strangled to bury with him; half their bodies buried below his; half, above in the common grave. When witchcraft was suspected in an illness or accident, women were accused first. When twins were born, when slaves were captured, when warriors got drunk on trade rum, the women suffered.

Yet, in the Calabar scheme of things, the women were more cruel to each other than the men ever thought of being!

This was especially true in the treatment of slaves and in the treatment of newer wives brought into the harem. And no one was more likely to accuse a woman of witchcraft and call for the bean trial than her sisters in the compound.

Other charms of Calabar included wild elephant herds which periodically tore down the grass and mud huts of the villages, millions of driver ants which defoliated the trees eating everything in their path, poisonous snakes of every size and description, crocodiles in the rivers to snap up anyone who fell out of a canoe, and hippopotamus herds in those same rivers to capsize said canoes.

Sure, Calabar was a beautiful country, but really, the chamber of commerce did not have a whole lot of material to work with, did it?

Why in the world would a lady want to leave home in civilized Scotland and go to a place like Calabar?

What could keep her there for 39 years as a missionary? Why would she choose to spend several of her furlough vacation times going deeper into the bush rather than returning home?

"God has been good to me, letting me serve Him in this humble way," Mary Slessor said. "I cannot thank Him enough for the honor He conferred upon me when He sent me to the Dark Continent."

What made her regard it as an honor to serve in such a scudzy place?

Mary Slessor had been converted as a child in Dundee, Scotland, where her father was an abusive drunk and her mother a factory worker. When she was 11 years old, Mary began working 12-hour shifts daily at the looms in the textile mill.

Mary Slessor had been converted as a child in Dundee, Scotland, where her father was an abusive drunk and her mother a factory worker. When she was 11 years old, Mary began working 12-hour shifts daily at the looms in the textile mill.

Her background made her both tough and tender in the right proportions.

During her off time from the mills, she helped teach a slum Sunday school Bible class for the Presbyterian Church. She also engaged in open air meetings though she was too shy to speak herself.

The exploits of David Livingston in Africa excited her devotion and for 14 years, she worked in the factory, learned to read, taught the slum children, and prayed to become a missionary.

She learned about conditions in Calabar through reading the Missionary Record, a magazine which in later years published many of her own letters and reports. In 1874, Livingston died and the next year Mary Slessor volunteered to the Scottish Missionary Society. She sailed for Calabar in 1876.

For the next 12 years she worked in the towns near the mouth of the Calabar River where she mastered the language, learned the customs of the place, grew spiritually, prayed and assisted senior missionaries.

"Blessed the man or woman who is able to serve cheerfully in the second rank ..., The test of a real good missionary is this waiting, silent, seemingly useless time," she wrote.

She regarded her long apprenticeship as a lesson in being Christian. Christ calls us to BE more often than he calls us to DO, she said.

She believed that the ordinary is as important to the Kingdom of God as the dramatic. "Everything, however seemingly secular and small, is God's work for the moment and worthy of our very best endeavor," she said.

She longed to engage in pioneer missionary work, to reach the unreached, to open new territories -- yet, she took her time, that is, she looked for God's own time.

"Christ was never in a hurry. There was no rushing forward, no anticipating, no fretting over what might be. Every day's duties were done as every day brought them, and the rest was left with god. 'He that believeth shall not make haste,'" she said.

In 1888, when she was 40 years old, the opportunity opened for her to travel up river by canoe into the bush country to minister to the Okoyong tribe. Circumstances dictated that she was the only missionary to enter that area. Because of the heat, this trip, like most of her travels in Africa, was done through the jungle at night.

When she arrived the village was deserted.

All the people were at a funeral. The chief's mother had died and when he returned he happily reported to the new missionary that he had given the old lady a grand send-off by killing 24 people to be buried with her. Four "witches" had died in the bean trial proving they had been responsible for her death.

"The tribe seemed so completely given over to the devil that we were tempted to despair," she wrote.

In order to win them to Christ, Marry Slessor abandoned her European clothing and dressed in the Calabar national custom. She seldom wore shoes. She ate the same food as the people she taught and drank unpurified water.

These practices injured her health but she felt that the more she could identify with the people the more they could focus on the content of her teachings.

"It is a real life I am living now, not all preaching and holding meetings, but rather a life and an atmosphere which the people can touch and live in and be made willing to believe in when the higher truths are brought before them," she said.

She build her own hut our of sticks and mud to live in. Her bed was a mat on the floor and she made cupboards, table and chairs our of mud molded into shape and dried.

"In a home like mine, a woman can find infinite happiness and satisfaction. It is an exhilaration of constant joy -- I cannot fancy anything to surpass it on earth," she said.

Why could she be happy in such a place?

"Life is so great and so grand; and eternity is so real and so terrible in its issues... All is dark, except above. Calvary stands safe and sure.... Life apart from Christ is a dreadful gift," she said.

"Christ is here and the Holy Spirit, and if I am seldom in a triumphant or ecstatic mood, I am always satisfied and happy in His love".

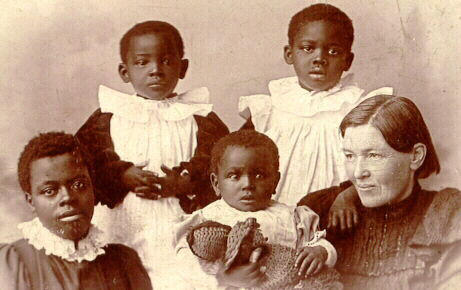

One of the first things she did in her new home was to begin collecting twin babies. She literally gathered castaway babies off the village trash piles. She raised dozens of sets of twins in her home. For years she was seldom without a baby in her arms whatever else she might be doing.

One of the first things she did in her new home was to begin collecting twin babies. She literally gathered castaway babies off the village trash piles. She raised dozens of sets of twins in her home. For years she was seldom without a baby in her arms whatever else she might be doing.

A crisis descended on the village when a falling log crushed the chief's son as during construction of a house.

Mary nursed the young man for days but he died anyhow and the tribe prepared for a funeral. People cowered wondering who would be sacrificed to be buried with him.

Mary Slessor insisted on preparing the body herself. She bathed the dead man and dressed him in the finest European cloths she could find in the mission box. She tied silk scarves around him, gave him a fancy hair cut, painted his face yellow, and crowned him with a top hat. Then she sat the body upright in a chair with a whip and a cane in his hands. She fastened a large umbrella over the chair and anchored a mirror in front. Then she called the chief and all the people to come see.

All admitted the display was a wonder but they still felt at least 12 people ought to be killed to go in the grave -- the bean trial was scheduled for the two days later.

Mary prayed.

"My life is one long daily, hourly, record of answered prayer. For physical health, for mental overstrain, for guidance given marvelously, for errors and dangers averted, for enmity to the Gospel subdued, for food provided at the exact hour needed, for everything that goes to make up life and my poor service. I can testify with a full and often wonder-stricken awe that I believe God answers prayer... (Prayer) is the very atmosphere in which I live and breathe and have my being, and it makes life glad and free and a million times worth living. I can give no other testimony. I am sitting alone here on a log among a company of natives.... Natives are crowding past on the bush road to attend palavers, and I am at perfect peace, far from my own countrymen and conditions, because I know God answers prayer. Food is scarce just now. We live from hand to mouth. We have not more than will be our breakfast to-day, but I know we shall be fed, for God answers prayer," she once wrote.

The evening before the prince's funeral, two missionary visitors chanced to come up river to call on Mary. They brought with them a magic lantern, which was a sort of slide projector that didn't use electricity. In honor of the dead man, they showed London street scenes.

This display impressed the crowd as the most magnificent send-off a dead prince had ever had. They agreed to place only one cow and one witch in his grave.

Mary convinced them to chain the witch in her house until the funeral. They agreed because her home was an unholy place because of the twin babies she kept, but they were still hell-bent on giving the accused woman the bean trial. People gathered from all over the district as word spread from tribe to tribe. Warriors tapped keg after keg of trade rum.

Tension mounted.

The poison beans were prepared.

Finally, the shy little Scotch woman marched out of her hut, snatched the bag of beans and stood the armed men down face to face.

The prince was buried in style -- but without any company save the cow. It was the first funeral in the tribe's history with no human sacrifice.

Such confrontations grew common. One lone woman and Christ against an army.

Once she halted an intertribal war by marching between the two opposing armies and demanding they pile their weapons at her feet. She collected a heap of spears, bows, arrows, clubs and knives five-feet high!

Was the missionary fearless?

Of course not. "I had often a lump in my throat and my courage repeatedly threatened to take wings and fly away --, though nobody guessed it," she said.

Was she faithful?

"If I have done anything in my life, it has been easy because the Master has gone before," she said.

Once she was traveling to a new village with a group of her baby twins. Thirty-three men paddled the huge canoe when a hippopotamus attacked. Dozens of men dove overboard to escape. Mary would not leave her babies. She grabbed up a tin dishpan from the supplies and pounded the beast on the nose as it tried to bite the canoe in half.

The startled hippo knew when it had bit off more than it could chew; it swam away.

"I don't live up to half the ideal of missionary life. It is not easier to be a saint here than at home. We are very human and not goody-goody at all," she said.

Her holy boldness earned the respect of the people; more and more of them turned to Christ.

A hymn she taught the people sums up her message to the people:

He came to save us from our sins.

He was born poor that He might feel for us.

Wicked men killed Him and hanged Him on a tree.

He rose and went to heaven to prepare a place for us...

Mary Slessor began building churches in the architectural style familiar to the tribes.

"We don't begin, or end either, with a house; We begin and end with God in our hearts," she said.

When a notorious bad guy came to a service, she chased him out yelling, "God has no need of the likes of you with your deceit and craft. He can get on quite well without you -- though you can't get on without God. Ay, you have that lesson to learn yet!"

The congregation cheered.

Once returning from furlough in Scotland, the other missionaries were surprised to find that her baggage and trunks were filled with few other supplies than cement. Her luggage was the only way she had to transport it.

She used it for church and mission buildings deep in the brush, but she had no training in cement work.

"I just stir it like porridge; turn it out, smooth it with a stick, and all the time keep praying, 'Lord, here's the cement; if to Thy glory, set it,' and it has never once gone wrong," she said.

When a delegation of hostile witch doctors and local kings came to inspect one of the church buildings to see if it were worthy of being allowed in their territory, she told them, "God will doubtless be immensely pleased and benefited by your wondrous condescension"!

This from a woman tender enough to raise over 50 abandoned babies. She felt that Christian missions demanded women tough and tender. She called for women to join missionary work:

"Consecrated, affectionate women who are not afraid of work or of filth of any kind, moral or material... women who can tactfully smooth over a roughness and for Christ's sake bear a snub, and take any place which may open. Women who can take everything to Jesus and there get strength to smile and persevere and pull on under any circumstances. If they can play Beethoven and paint and draw and speak French and German -- so much the better. But we can want all these latter accomplishments if they only have a loving heart, willing hands, and common sense," she said.

When the new invention of radio came on the scene, Mary Slessor drew parallels between it and the Christian life.

"We can only obtain God's best by fitness of receiving power," she said. "Without receivers fitted and kept in order, the air may tingle and thrill with the message, but it will not reach my spirit and consciousness."

She constantly strove to be tuned in and receive from God.

Yet, she knew the frustration of not seeing prayers answered to her immediate satisfaction. She wrote a friend:

"I know what it is to pray for long years and never get an answer -- I had to pray for my father. But I know my heavenly Father so well that I can leave it with Him for the lower fatherhood...

"You thought God was to hear and answer you by making everything straight and pleasant -- not so are nations or churches or men and women born; not so is character made. God is answering your prayer in His way...

"The gate of heaven is never shut."

For a time, she was engaged to marry another missionary but they broke off their engagement when he decided to work in another field. She lived and worked alone most of her life. She found enjoying good things alone more difficult that facing hardship:

"When you have a good thing, or read a good thing, or see a humorous thing, and can't share it, it is worse than having to bear a trial alone," she said.

Throughout her ministry one of the biggest trials she faced was convincing the tribes to abandon the bean test. She intervened in numerous ways. And as she saved people's lives, more and more people began to turn to her to settle their disputes and to give them justice.

Because she was tough but fair she became the only white person many of the tribes trusted. The British colonial government recognized her stature and appointed her as a judge.

On being appointed to court she said, "It will be a good chance to preach the Gospel and to create confidence and inspire hope in these poor wretches who fear white and black man alike;, while it will neither hamper my work nor restrict my liberty."

By demonstrating a better way than the bean to try every crime from chicken theft to murder she influenced the eventual abandonment of ordeal by beans.

Her letters and reports to the Missionary Record Magazine earned her world wide fame. She became as fame as David Livingston in her day. Donations poured in for her work. She used the money to build homes for abandoned twins, battered wives, and a hospital.

Many of the twins she had rescued as infants, she saw grow to adulthood, marry, go to college or become Christian workers.

Not only did the tribes and the colonial government honor her, but King George V awarded her the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem.

She kept the honor secret from her fellow missionaries until telegrams of congratulation began pouring in from all over the world.

"I have lived my life very quietly and in a very natural and humble way. It isn't Mary Slessor doing anything, but Something outside of her altogether uses her as her small ability allows," she said.

She felt uncomfortable at being addressed as Lady Slessor and said, "I am Mary Mitchell Slessor, nothing more and none other than the unworthy, unprofitable, but most willing, servant of the King of Kings."

Although her health was failing and she could no longer walk, she designed a box on wheels which her friends used to transport her from church to church in her mission district.

This chariot made life easier in some aspects but she continued to suffer a few hardships. One night her diary closed with the happy entry: "My heart is singing all the time to Him Whose love and tender mercy crown all the days". Later that same night a massive colony of biting driver ants dropped from the thatched roof onto her bed and chased her from the room.

Working right up to the end, she died on January 13, 1915.

Among her last words were these:

"I should choose this life if I had to begin again: only I should try to live it to better purpose.”

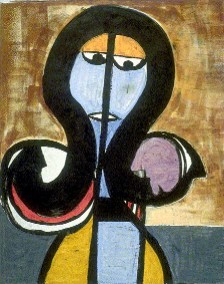

Today she is remembered and commemorated by a monument in Dundee, Scotland; by a painting of her made 70 years after her death by Nigerian artist Rufus Ogundele; and by the Mary Slessor Foundation which even now carries on the work she started.

For more information about Mary Slessor try these links:

http://www.maryslessor.org/index.html

http://www.dundeecity.gov.uk/centlib/slessor/mary.htm

-----------------------

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at