JACKSONVILLE'S RAILROAD HISTORY

c.2005

by

John W. Cowart

In 1882, George M. Barbour rode a train from Jacksonville to the end of the line out in the pine woods -- it was a bad trip.

Barbour -- who was NOT a member of our Chamber of Commerce -- recorded impressions in his book Florida For Tourists, Invalids and Settlers:

"The entire trip that day was through an unsettled region, the only human beings living along the road being... families of Florida natives, genuine, unadulterated Crackers -- gaunt, pale, tallowy, leather-skinned, stupid, stolid, staring eyes, dead and lusterless; unkempt hair, generally tow-colored; and such a shiftless slouching manner! Simply white savages... Stupid and shiftless, yet sly and vindictive, they are a block in the pathway of civilization, settlement and enterprise wherever they exist," he said.

Then he said some really nasty things about Florida women concluding with "... No underwear whatever!".

However, he did like the people of Jacksonville and told why:

"The society of Jacksonville is universally admitted to be unusually select, cultured and refined," he said, "The reasons are not far to seek: Many of the most prominent citizens have been drawn thither from all parts of the country and are not native Floridians."

We love you too, Mr. Barbour.

Perhaps, Mr. Barbour's railroad experience upset him.

"It was enlivened," he said, "By the car setting off the track two or three times, caused by the breaking of the old wooden rails. On such occasions the male passengers would cheerfully assist the ... conductor to replace the car and hunt up and lay a fresh rail. (They) seemed to consider it a part of the business of the trip."

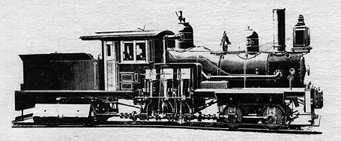

Barbour does not mention which kind of engine pulled his car over the wooden rails. During the early days of rail roads in North Florida, the various railroad companies used several kinds.

The earliest railroads used mules to pull the cars over the track. In rural areas, men stood in the cars, three on each side, and polled along much as they would if they were moving a flat-bottomed boat through shallow water.

The first rails were simply wood but later iron strips were nailed on top of the rail. This helped the tracks last longer but presented new problems.

As a young man, H.E. Lagergren worked passing wood to the fireman in a Florida Railway & Navigation Co. engine; for years he watched the development of railroads in the sunshine state. In 1879, he settled in Starke and, in his old age, wrote several letters about his memories of railroading's early days.

"The roads were build by slave labor, hired from planters. Their only equipment, even for high fills, were shovel and wheelbarrow," he said. "When they died they were dumped in the track and buried beneath the ballast".

When iron strips were added to the tops of wooden rails, Florida heat caused the strips of iron to curve up where the rails joined. These "snake heads" as they were called caused super bumps as the trains passed over.

"If the snake head was only two or three inches, it didn't matter much because the train traveled so slowly anyway," Lagergren said. "More bend than that, however, had to be straightened. The rail was taken up and heated over a fire made of old cross ties, hammered straight and replaced."

Snakes heads made for a delay but so did alligators. Lagergren recalled a big gator getting stuck in a drainage culvert causing a flood which wiped out a half-mile of track.

Swamp grass grew so high along the tracks that on windy days it blew over the rails making them so slippery the engine couldn't move.

"The engineer... had to carry a bucket of sand... he had to sprinkle the rails with sand to gain enough traction to pass," Lagergren said.. "among his other standard equipment was a bag of hominy (grits) or rice -- not for dinner but to toss in the tender tank to stop leaks!"

"The engineer... had to carry a bucket of sand... he had to sprinkle the rails with sand to gain enough traction to pass," Lagergren said.. "among his other standard equipment was a bag of hominy (grits) or rice -- not for dinner but to toss in the tender tank to stop leaks!"

When wood for the engine ran low, crew and passengers stopped and cut pine trees for fuel to continue their journey.

Lagergren told about passengers building fires on the floors of the cars to keep warm in winter and about how mosquitoes and sand gnats forced them to ride with all windows shut in summer. Boys boarded the trains at whistle stops to sell "Ile o' Pennyrile", an insect repellent. They always sold out.

Some early trains did not have seats in the cars, but passengers carried rocking chairs to sit in as they dashed along at high speed.

Speed?

Yes, in 1877, an engineer was fired from the St. Johns Railroad Co. for endangering company equipment by driving too fast; he was clocked chugging along at seven miles per hour!.

A lady passenger on that railroad complained, "The engine was so small that if a cow strayed on the tracks, the engineer has to dismount from the cab and drive the animal off with a cattle whip". She also said that passengers shot alligators from the train for sport as it passed through the swamps.

A lady passenger on that railroad complained, "The engine was so small that if a cow strayed on the tracks, the engineer has to dismount from the cab and drive the animal off with a cattle whip". She also said that passengers shot alligators from the train for sport as it passed through the swamps.

As the railroads pressed south along the coast, feeding passengers became a problem. The Lagergren said the railway solved that problem by having a small ship sail parallel to the coast to meet the train with food at various places along the beach.

These conditions, though they seem primitive to us, represented a great improvement over previous travel through the wild scrub, marsh and uncut jungle of 19th Century Florida. The state wanted railroads from the earliest days.

As early as 1834, Isaiah Hart, founder of Jacksonville, and other leaders attempted to connect Jacksonville with the Gulf Coast. Their proposed railroad was to be called the Florida Peninsular and Jacksonville Railroad. The first leg was to be from Jacksonville to Alligator Town (now known as Lake City). Seminole Indians attacked the area, and the railroad investors lost over a million dollars as their project had to be abandoned.

In 1852, Dr. A.S. Baldwin lead another group of investors to build the Florida, Atlantic & Gulf Central Railroad to Alligator Town. A yellow fever epidemic delayed the railroad's construction until 1860.

Then came the Civil War which left area railroads in a shambles.

Scads of little railroads laid a few miles of track here and there out of Jacksonville before they were abandoned, merged, or were bought up by other railroads.

In 1875, F.O. Sawyer came to Jacksonville aboard a Jacksonville, Pensacola & Mobile Railroad train. He later became secretary of the Jacksonville Terminal Co. In 1937, he wrote an account of some of the rail companies he had seen pass through Jacksonville:

"In 1884, The Florida Central & Western Railroad Company, the Florida Western Railroad Company, and the Peninsular Railroad Company were consolidated into one railroad system under the name of the Florida Railroad & Navigation Company, V.C. Hoenning, President.

"In 1885, the F.R.&N. Ry. System went into the hands of a receiver, Col. H.R. Duval, and in 1888, was sold, which sale included the Florida Central & Western Railroad running from Jacksonville to Chattahochee, branches to St. Marks and Monticello, Florida, and all terminal property in Jacksonville, being purchased by W. Bayard Cutting & Associates and merged into the Florida Central & Peninsular Railroad System, H.R. Duval, president, under which name it operated until purchased by Seaboard Airline Railway Company," Sawyer said.

In some ways the story of railroads in Jacksonville gets even more complex than that; in other ways it gets simpler. Rail history buffs enjoy tracing trains through such detailed histories as Mr. Sawyer's. For the rest of us, a few simple pegs served to outline that history.

For instance, fuel.

Woodburning engines replaced mules in pulling Florida's trains. Then coal became the fuel of choice, then oil, then diesel-electric locomotives appeared on the scene.

Another way to look at Jacksonville and the railroad is to look at some of the men involved in bringing railroads to Florida. You will already have noticed that some of these men, such as Baldwin and Bayard, have north Florida communities named for them.

Another such railroad pioneer with a town named for him was David Yulee, who is sometime called the father of Florida's Railroads.

During his term in the Florida Legislature, Yulee pushed for passage of the far-reaching, Internal Improvement Act of 1854. This legislation enabled the state to grant land to railroad companies which contracted to lay track into pioneer areas. It also helped railroads through bond issues.

Picking up vegetables in the fields

As railroads moved into new areas, settlers and tourists could be brought in, the U.S. Mail could reach towns quickly, lumber and phosphate could be exported, and Florida's fruit and vegetables could move to northern markets before they spoiled.

As railroads moved into new areas, settlers and tourists could be brought in, the U.S. Mail could reach towns quickly, lumber and phosphate could be exported, and Florida's fruit and vegetables could move to northern markets before they spoiled.

Also, successful railroad companies could rake in millions.

Yulee built his own railroad linking the port of Fernandina with the timber sawmills of Cedar Key. Yulee's venture was Florida's first cross-state railroad. It survived the Civil War and lasted until 1932 when it was bought, then abandoned, by Seaboard Air Line.

Florida ship owners were not crazy about railroads which took away their business. Back when Florida was a territory, boating interests sponsored and passed a law forbidding any railroad from crossing the state line. After the Civil War, the state chose to enforce this law to keep companies owned by damn yankees out.

On November 4, 1879, Henry B. Plant, a yankee, bought the Savannah, Florida & Western Railroad, headquartered in Savannah, and the Waycross & Florida Railroad, headquartered in Waycross.

On November 4, 1879, Henry B. Plant, a yankee, bought the Savannah, Florida & Western Railroad, headquartered in Savannah, and the Waycross & Florida Railroad, headquartered in Waycross.

Florida closed the border to his trains.

The rail magnate huffed and puffed.

Florida still would not let him in. So he bought a new railroad, the East Florida Railroad, headquartered in Jacksonville.

His Jacksonville railroad laid track north. His Waycross railroad, now called the Waycross Short Line, laid track south. When they came to the St. Mary's River, the Jacksonville railroad built a dock to the middle of the river. The Waycross railroad built another dock to the middle of the river. Coincidently, the two docks touched in midstream and while the two railroads remained legally separate, trains from the north could finally come to Jacksonville.

Plant, for whom Plant City is named, bought, sold, resold, merged and dealt his way through at least seven railroad companies. He died in 1899 and his holdings were sold to Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co. in 1902.

The year before, on February 28, 1901, one of Plant's engines raced a Seaboard Coast Line engine; the government used the contest to award the U.S. Mail contract.

According to Robert W. Mann's excellent history u Rails 'Neath The Palms, Plant's engineer, Albert H, Lodge, had but one order, "Win the contract!"

"Georgia passed like the wind as the train sailed along... Officials checked their timepieces against the mile posts. As the train ripped past the siding, the men's faces, flush with excitement or ashen with fear, grew into a solid expression of enthralled joy -- they calculated the speed at a steady 108 miles per hour," Mann said.

Lodge drove his engine the 148 miles between Fleming, Ga., and Jacksonville in 134 minutes. He not only won the contract, he also set the United States speed record of his day.

There is no north Florida town named for Henry Morrison Flagler -- a whole county carries his name. Perhaps that indicates the size of his stature in the area's railroad development.

Henry Flagler came to Florida as a tourist in the winter of 1883. When he arrived he was already a millionaire as a founder of the Standard Oil Company, and he was 53 years old.

Henry Flagler came to Florida as a tourist in the winter of 1883. When he arrived he was already a millionaire as a founder of the Standard Oil Company, and he was 53 years old.

Flagler fell in love with Florida's First Coast.

He loved the climate; he loved the history; he loved the people; he loved the ambiance; he loved the opportunities he saw in north Florida. And the more he saw of the state, the more he loved it.

A grand vision obsessed him.

He envisioned the area as an "American Riviera" centered in St. Augustine with luxurious resort facilities to rival anything Europe's Riviera had to offer.

Flagler began constructing such resort hotels in St. Augustine, the Ponce de Leon, the Alcazar, the Casa Monica, later named the Cordova. These were to be the most lavishly beautiful resorts in America.

Flagler's plans hit a snag.

Two snags really: one was that to transport the finest building materials to St. Augustine, he had to use undependable ships or an even less dependable narrow gage railroad. Besides, how were wealthy tourists and the cream of American society to get to his hotels?

To kill this two-headed snake, in 1885 Flagler bought the little Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Halifax River Railway. He widened the tracks to standard size, fenced the tracks to keep cows off, laid heavier rails, and modernized the railroad's equipment.

Before this, each railroad company decided on the width of its own track so trains from one company could not run on track owned by another company; in 1888, most of the various companies agreed to lay track 4 feet 8 inches apart. This standard gage meant trains could run from one end of the country to the other.

Therefore on January 9,1888, the same year Flagler opened his Ponce de Leon Hotel, the first through, all Pullman vestibule train, named "The Florida Special" left Jersey City for Jacksonville with 82 passengers. It made the run in only 29 hours and 50 minutes; before this, it took a train 90 hours to make the same trip.

Goodbye to the old mule trains with mosquito repellent for sale.

Welcome the day of opulent luxury in rail travel.

While not exactly enjoying Amtrak (which came on the scene in 1971) service, passengers on the 1888 Florida Special managed to make do

.

On Tuesday, Jan. 10, 1888, The News-Herald of Jacksonville, the city's newspaper of the day, described travel conditions on the Florida Special:

"Good judges among railroad men say that it is one of the finest trains ever seen... The train consists of four sleepers, a dining car, a combination car and a baggage car. The engine No. 67 that pulled this train was one of several built to order for this express work and is a magnificent piece of railroad machinery...

"The baggage car is large and fine and finished in oiled woods... Just beyond this are 12 berths. The beauty of the work and finish is what attracts the attention of the beholder at first. The seats are elegantly upholstered in pale blue and in fine style. The sides are finished in Spanish mahogany which give a very rich setting. The berths and the outsides are finished in birds'eye maple burnished to the smoothness of glass, which reflects all objects like a plate mirror. The windows are double of fine French glass, and between them is set long, narrow bevel edged plate glass mirrors. The lambrequins over them match the plush of the seats...

"Overhead are exquisite chandeliers with delicate opaque glass globes, and also the pear shape globes of the incandescent light. The roof of the car inside is a raised deck ceiling beautifully carved and decorated in Queen Anne style in a most elegant and fanciful way...

"At the end of the smoking room is a neat and compact buffet for wine... the chairs are of light cane manufacture and the plush is cherry and the window lambrequins the same. At the opposite end, on either side of the entrance are book cases... also a writing desk, well stocked...

"In The dining room (which rivals Delmonico's) ... with seats for 30 to 40 people.. the entire car is handsomely fitted up in Nile-green silk plush ...in the most elegant manner possible and nothing that can be added to the comfort and pleasure of the passenger is omitted..."

This one train sported more electric lights than the whole city of Jacksonville at the time!

A belt around the axle of the baggage car turned a dynamo lighting 20 "Edison Incondescent, 60 watt lens" in each car. And every car was heated by steam pipes drawing directly from the engine.

This is the train President Grover Cleveland and his wife traveled on when he visited Jacksonville for the 1888 Sub-Tropical Exposition.

Visitors to Flagler's resort hotels found there was only one small hitch in getting to them in luxury -- the St. Johns River. They had to disembark in Jacksonville, cross the river by ferry boat (which Flagler owned), and board a smaller train in Southside for the rest of the trip.

This wouldn't do at all.

To eliminate this inconvenience, in 1889, Flagler began construction of the first bridge across the St. Johns. His steel-railroad bridge opened for traffic on January 20, 1890. In 1925, it was replaced by the railroad bridge that runs parallel to Jacksonville's Acosta Bridge.

Flagler had a thing about railroad bridges; as his resort hotel empire pushed south to resorts at Ormond, West Palm Beach, and eventually to a barren place in the sand dunes called Miami, Flagler extended his railroads to follow. By 1912, he had built a railroad over trestles all the way to Key West. A hurricane in 1935 wiped out the tracks and the state used the old railroad pilings to build the Key West Highway.

Flagler laid the foundation for the mighty Florida East Coast Railway Company; but the railroad fell into hard times and receivership.

In 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission awarded the railroad to Edward Ball, an associate of Alfred I. duPont.

The Florida East Coast Railway lost $4.8 million the year before Ed Ball took it over. Ball bought its default bonds for 7.5 cents on the dollar; the very next year, the railroad showed a profit.

He brought in new people, abolished old work rules, restructured pay rates, untangled and reduced FEC debts, installed automatic crossing gates, initiated new safety procedures, improved rolling stock, upgraded equipment, and built a spur to serve NASA's space program at Cape Kennedy.

He managed the railroad through a bitter union fight which lasted 12 years, the longest strike in American railroading. There were over 300 incidents of violence during the strike including 82 trains dynamited.

Now, another thing which Henry Flagler thought Jacksonville lacked to accommodate his railroads and tourists was an elegant train depot.

He began to put that to rights as early as 1890 when he began to secretly buy property, mostly marsh land west of the city, for his envisioned Union Depot. Whipping other railroad owners into line and obtaining a public bond issue, Flagler organized the Jacksonville Terminal Company in 1894.

The Jacksonville Terminal of the Great Union Railroad opened in 1919. It is an impressive structure featuring a 180-foot facade of 14 Doric limestone columns that rise 42 feet from the floor. Inside, a 75-foot barrel-vaulted ceiling greeted the passengers which detrained from the more than 200 trains a day that served as the gateway to Florida during its heyday. The last train departed Jacksonville Terminal on January 3, 1974.

Marsh was filled in with 300,000 cubit yards of earth and 2,100 pilings -- some driven 70 feet deep. A wooden train-shed over a fifth of a mile long was built -- but a hurricane blew the whole thing down.

The Union Depot, done in Open Mission style and decorated with wrought iron and palms, opened on January 15, 1897. Only one small tower of this original structure remains on the north side of today's Prime Osborn III Convention Center.

The old train station that was converted into Jacksonville's Convention Center, was built around the original Union Depot in 1919. It sported 14 sandstone columns at the entrance with a main waiting room measuring 80 by 125 feet. Its ceiling (rumored to be the eighth highest unsupported ceiling in the world, is 70 feet above the floor. At its heyday, Union Station had 60 miles of track and 29 track stations for passengers.

Curiously enough, Henry Flagler himself may have been obliquely responsible for the station's decline -- In 1896, he bought a White Steamer Motor Car and later brought it to Florida. Flagler died in West Palm Beach at age 83 in 1913.

Who can tell the impact of the automobile on railroading?

Of course, to a certain extent, the auto-train relationship in Florida has been symbiotic. According to material supplied by Gloria S. Taylor, FEC personnel administrator, in September, 1988, The Florida East Coast Railway Company took delivery of 51 new auto rack cars to transport new automobiles over the nation. Forty-one of these new racks were assigned to Ford national Pool and 10 were assigned to Chrysler National Pool.

Other FEC innovations include the use of concrete railroad ties instead of wooden ones. The new ties have a projected lifetime of a half century. FEC also is using 50 new all-aluminum flatbed trailers allowing the railroad to haul more payload and be more competitive; these new flatbeds brings the total FEC owns to 319.

Another railroad giant in Jacksonville is CSX Transportation.

Seaboard Air Line and Atlantic Coast Line, rival systems for 140 years, merged in 1967. Seaboard Coast Line took control of the Louisville & Nashville and other smaller railroads in 1971 to form the Family Lines System. On November 1, 1980, the Chessie System and the Jacksonville-based Family Lines/SCL system were joined under the new CSX Corporation.

Railroad historian Robert W. Mann's Rails 'Neath The Palms sums up the birth of CSX Rail Transportation in a nutshell:

"The modern railroad may indeed be a colorless thing compared to its past," Mann said. "It has become a creation of plastic and high-gloss sameness, as endless strings of truck vans slip past on rails anchored to concrete -- devoid of clickety-clack, devoid of the red caboose and multi-engine lash-ups. the rails of Florida entered a new age with the end to end merger of the giant Chessie System on November 1, 1980, and more recently the complete absorption of all Family Lines member roads into a single Seaboard System Railroad. From that point on, things will never be the same."

No, Jacksonville railroading will never be the same; but a bright future lies ahead.

On March 29, 1989, CSX Rail Transportation opened its Kenneth C. Dufford Transportation Center, named for CSX Rail Transportation's executive vice president.

The transportation center features a three-tiered control center in a circular room with a 150-foot diameter. There, through an ultra modern computer system, dispatchers can control as many as 1,400 trains a day.

"It looks like Star Wars in there," said Norm Going, CSX Transportation's manager of corporate communications. "It's amazing. We control nearly 20,000 miles of track in 19 states from that one building right here in Jacksonville. It's the wave of the future."

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at