YELLOW JACK IN JACKSONVILLE:

The 1888 Epidemic

c. 2005

by

John W. Cowart

On July 28, 1888, Yellow Jack invaded Jacksonville, Florida.

His first attacked Mr. R.D. McCormick, a visiting businessman who was registered at the Grand Union Hotel.

Within two weeks the monster controlled the city.

Within two weeks the monster controlled the city.

The invisible killer slaughtered whole families of rich and poor without discrimination or apparent reason. He seemed to strike at his own cruel whim and no one knew where he came from or how to stop him.

Yellow Jack was the personification of yellow fever.

Newspaper cartoons of the day pictured him as a skeleton shrouded in wispy graveclothes and wearing a yellow sombrero, which indicated his supposed Cuban birthplace.

Yellow Jack’s arrival in Jacksonville confronted every citizen with two equally horrible alternatives: staying home to face the epidemic, or trying to flee past quarantine guards armed with shotguns who sealed all exits from the city.

“One road leads to Hell and the other to damnation. And whichever one you take, you’ll wish you’d tuck the other,” said the Sept. 4, 1888, Florida Weekly Times newspaper.

Most citizens tried to escape.

The very next day after Yellow Jack’s first appearance here, the Florida Times-Union reported, “Every train and steamer going out is loaded to the utmost capacity, and drays, carriages and wagons laden with trunks, furniture and people roll depot-ward all day”.

W.C.B. Solee, who remained in the city, said, “When the trains pulled out they were jammed with refugees – packing the platforms, hanging on to the guardrails, and even clambering up on the tops of cars.

“In many of the residences of my friends, which I went through afterwards to make secure, I found food in vessels ready to cook, and bureau drawers partially emptied and left wide open”.

Elihu Burritt, who wrote Experiences In A Stricken City, said that during the tourist season of 1887/88, “More than 130,000 people registered at hotels in Jacksonville”.

But, in a Sept. 19th letter to a friend, Patrick McQuaid, a candidate for a second term as Jacksonville’s Mayor, wrote, “The situation is now terrible… over 150 new cases yesterday and 20 deaths… All business and work is suspended… The city government is virtually defunct, the heads having fled… God knows where the end is”.

The Florida Minstrels, an 1880s theatrical group, later made up a song about the panic:

De Mayor’s proclamation

didn’t do a bit of good,

Kase all de oldest citizens was

breakin’ for the woods.

You never seen so many folks

at the Duval County Fair,

As run aboard de steamboats

in the Yaller Fever Scare.

As the population of Jacksonville dropped from over 130,000 people to 14,000, those hoping to escape faces a massive quarantine which grew ever tighter.

Everyone in Jacksonville was in a high-risk category; no one in other cities wished to be contaminated by refugees from Jacksonville.

Stories of horror and stupidity about the treatment of Jacksonville refugees filtered back to the city and were printed in the daily newspapers:

Fearing that a suspect freight shipment might carry the fever, “The City Board of Marianna recently fumigated a half-ton of ice that was put off at the depot there… Some of the Board suggested it ought to be dumped into a large vat and boiled,” reported the Weekly Times.

The mayor of Montgomery, Alabama, offered a $100 reward to anyone capturing an escapee from Jacksonville.

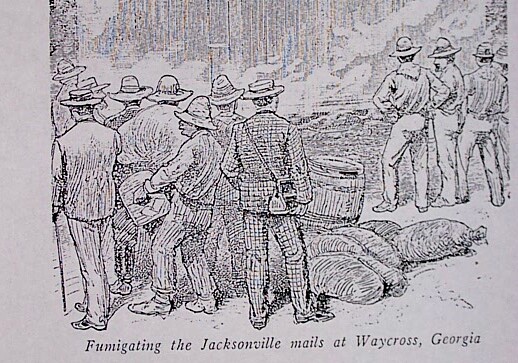

Waycross, Georgia, citizens threatened to pull up the tracks if a train from Jacksonville tried to pass through even if it ran a t full speed with the passengers locked in and the windows sealed.

Officials in Ocala wrote a letter published in the August 12th Times-Union saying, “We condole and sympathize with Jacksonville on her misfortunes and afflictions, but self-preservation is the first law of nature”.

Many other cities felt the same way.

Refugees from Jacksonville were shot at, turned back or locked in cattlecars in various places. Guards armed with shotguns sealed all roads out of Jacksonville and refugee camps were set up to detain escapees under quarantine. Trains were rerouted around the city and steamboat lines suspended  service.

service.

“Nowhere was a manly hand extended. If they had been in the land of the Hottentots they could hardly have fared more wretchedly,” said J.E. Drayton concerning the treatment of his family and a trainload of refugees who had left Jacksonville on the first day of the panic.

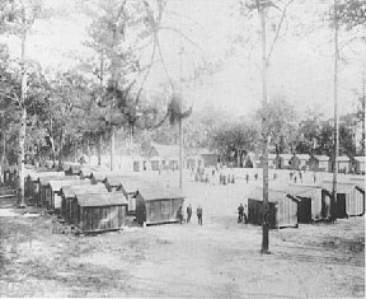

The 1888 photo here shows Camp E.A. Perry, a yellow fever detention camp on the south bank of St. Mary's River in Florida, near the Georgia border.

The Weekly Times editor wrote, “My advice to the people of Jacksonville… is to remain at home ‘til the fever scare subsides… It is much safer to fight the fever than to fight the fear of it”.

On the other hand, the Florida Dispatch urged people to flee; it published the advice of the Jacksonville Auxiliary Association, a health organization which virtually ruled the city: “The committee proposed to urge all persons to leave town as soon as they had places of refuge open to them”.

A September 8th Times-Union editorial said, “We advise all who can get away… to do so… Nothing now, it seems, can stay the plague except the want of material for it to feed upon”.

Such confusing and conflicting advise bewildered citizens.

One correspondent said, “You may stay in Jacksonville and catch the fever or try to run away and catch fits…

“Our invaders (the Yellow Jack microbes) drive us with their spears into the sea; the waves rise upo and drive us back again upon the cruel spears of the invaders and of all men we are most miserable”.

No one living at the time knew the cause or cure of the disease.

The Florida Dispatch explained the theory of “Wiggins, the Canadian weather prophet crank” who said:

“The cause of the fever is astronomical. The planets were in the same line as the sun and earth and this produced, besides cyclones, earthquakes, etc., a denser atmosphere holding more carbon and creating microbes.

“Mars had an uncommonly dense atmosphere, but its inhabitants were probably protected from the fever by their newly discovered canals, which were perhaps made to absorb carbon and prevent the disease”.

Reputable scientists were not much closer to the mark.

Mrs. H.K. Ingram, speaker for the American Association For The Advancement Of Science, recommended “exploding a little gunpowder on a shovel in the middle of the room” to combat the illness.

“It (the cause of yellow fever) is either a germ possessed of animal or vegetable life,” she said. “Or it must be a poison in the air in the form of a gas. If it be not animal, it may be fungoid… If the cause of infectious diseases be poisonous air or gases, concussion still becomes a most reasonable remedy”.

That theory sounded reasonable to a lot of people.

The federal government sent cannon from the garrison at St. Augustine to “concuss” the microbes. The Wilson Battery, a local paramilitary unit, set up the artillery on Jacksonville street corners and blasted Yellow Jack every five minutes all night every night. “The result was great damage to store windows and fronts while the fever raged on”.

Effigies of Yellow Jack were burned on street corners.

“Just before sundown last evening the proprietors of the Times-Union caused several bonfires of pitch and tar to be lighted about the building in order to purify the atmosphere in the vicinity… later in the evening other fires were lighted in different points in the city… Let fires be kept burning constantly,” urged the August 12th Times-Union.

Two days later the newspaper suggested such conflicting precautions as:

Nothing worked.

“Yellow Jack Reigns Supreme” declared one headline.

Excerpts from the sick lists published daily in the papers show the democratic scope of the disease: citizens of all ages, races, religions and economic status were victims.

Yellow fever attacks the liver and kidneys causing the skin to turn yellow and the stomach to hemorrhage producing a black vomit – the dreaded hallmark of yellow fever. The victim’s whole body turns black at death.

Caroline Standing, matron of Nurses at St. Luke’s Hospital, later recalled the fate of a city fireman, who did not flee the scourge: “William Craugn was found sick in the middle of (Forsyth) Street, in the last stages of the fever. He was lying prostrate, with his head down, his face red and yellow, showing the marked characteristics of the fever. He was partially delirious… with the symptoms of the fatal black vomit… He died the following morning”.

Before the disease ran its course nearly 5,000 of the 14,000 people remaining in Jacksonville caught it and more than 400 died. During a single September week, there were 1,000 new cases and 70 deaths; on just one day, 156 new cases and 20 deaths were recorded.

Times-Union editor Edwin Martin wrote:

“As believers in the great truths of Christianity, we should, on… the threatened prevalence of a dread pestilence in out midst, recognize our dependence of the Great Physician whose skill reaches even beyond the span of human life… It becomes the people of Jacksonville to bow themselves in all humility before the throne of grace and pray to Him who holds the universe under His control to stay the pestilence and save our city in this hour of danger. But should it not be consistent with His will to avert the epidemic, we can ask in all confidence for the sustaining strength to endure”.

Yellow Jack killed Martin a few weeks later.

To help Jacksonville endure the scourge, James Jaquelin Daniel, a leading citizen, organized the Jacksonville Auxillary Sanitation Association (JASA). “There is nothing which Jacksonville more needs than that her people should stand together in all matters pertaining to the welfare of their city,” he said.

Yellow flags marking houses containing the sick flew all over the city, and black bunting draped hundreds of doors. Death carts rattled through the city each night picking up the dead secretly to avoid spreading panic.

“Almost every household has been invaded by the pestilence and more than one family has been literally swept from the face of the earth. They dying have rarely been surrounded by loved ones and the dead have been interred with little if any ceremony,” lamented one sufferer.

Mass burials in trenches became necessary. Present-day workers near the intersection of 44th Street and Norwood Avenue occasionally still unearth skeletons of fever victims buried in these unmarked trenches.

Early in the epidemic, Daniel had urged citizens to “show the world that we have confidence in our own resources”. And Jacksonville responded. Pastors stayed to minister to their congregations, doctors labored without pay, businessmen contributed to the JASA, and a private citizen – Mrs. A.B. Anthony – went from house to house carrying jugs of fresh milk to the sick at her own expense.

After weeks of such efforts, Daniel issued a call for outside help and the nation answered Jacksonville’s distress call.

Other cities did what they could do to relieve suffering Jacksonville.

Editorial cartoons of the day portray Jacksonville as a stricken lady surrounded by Amazon warriors with raised shields giving her aid. Or they show Yellow Jack ravishing Lady Jacksonville with the whole nation, Columbia, fighting for her virtue.

Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, dispatched nurses into the danger zone. Jacksonville

A contingent of 18 Red Cross nurses from New Orleans took a train to come relieve suffering in Jacksonville, but the train engineer refused to stop in the plague zone.

It was after midnight in a torrential downpour when the nurses jumped from the moving train in MacClenny in order to reach the sick who needed them.

They stayed in this area for 79 days often working shifts of 72 hours without sleep. Some carried patients on their backs for miles to seek help. These nurses earned $3 a day.

Apparently, eight of them died of the fever.

Clara Barton wrote of their sacrifice, “Warm appreciation and grateful acknowledgement of the faithful hands that toiled and the generous hearts that gave”.

Some cities sent artillery to help blast the air. From all over the country money flowed in ranging fro9m large gifts to two cents sent by a widow contributing her mite.

J.J. Daniel caught the fever and died. Grieving citizens planned to erect a statue honoring him, but when the money was collected -- $2,000 in 48 hours – they chose a memorial more appropriate to his life and service: Daniel Memorial Orphanage And Home For The Friendless came into being.

“Great calamities… serve to bring the people to a practical realization of their dependence on the Creator. We believe this has been peculiarly true here in Jacksonville. This epidemic has developed many Christian heroes—we may almost say martyrs… This epidemic is daily illustrating the power of God, the influence of genuine religion and the brotherhood of mankind,” said the September 30th Times-Union.

Maybe so.

But heroes of faith found that their opposites also abounded in Jacksonville at the height of the plague.

“Antonio Christopher at the time he was taken sick with the fever is reported to have $3,000 in cash… False friends secured his pile and made off with it,” reported that same issue of the newspaper.

When H.L. Robinson, an employee of Western Union, died, two women, both claiming to be his wife, came forward to collect the salary due him. Neither woman had been aware of the other’s existence; confusion and feelings of betrayal mingled with their grief.

“Please find enclosed 50 cents, the joint contribution of two poor men for the Jacksonville sufferers,” said one letter the JASA received – the enclosed coin was counterfeit.

In October, the long confinement in a stricken city with a scarcity of supplies, drove people to form a mob.

About a thousand strong, they staged a raid on the JASA warehouse. The cannon of the Wilson Battery, previously used to concuss Yellow Jack, were now turned on his victims.

“Two guns were planted in the alleyway, loaded to the muzzles with slugs, shot and ten-penny nails. This information was conveyed to the insurgents, who were further informed that action would be instantaneous with the first move in the direction of the supplies. Thus peace prevailed, and what looked like the beginning of a bad riot was averted,” the newspaper reported.

William F. Hawley, who caught the disease but survived it, later recalled other people’s reactions to Yellow Jack.

Hawley and a friend heard a rumor that drinking champagne prevented the disease. They “vaccinated” themselves with six bottles in one night. Hawley could not remember whether or not his friend caught the fever, but, “I know he had a large headache the next day,” he said.

Finally, on November 25th, 1888, the temperature fell to 32 degrees and the cold weather did what batteries of cannon could not do – it killed the mosquitoes that carried Yellow Jack and ended the epidemic.

carried Yellow Jack and ended the epidemic.

It was to be another dozen years before Dr. Walter Reed would prove that mosquitoes were the disease vector and that killing them killed Yellow Jack.

“The Clyde Line steamboats… resumed operation on December 15th, and that night there was a welcoming reception. The Wilson Battery came out and shot off several salvos. There was a parade and a good time generally,” Hawley said.

The nightmare had ended.

As people returned to their homes, resumed business, greeted friends and talked about their experiences during the plague, perhaps a few remembered the last verse of the Florida Minstrels song:

It’s mighty curious, somehow,

But den it am a fact,

Dat dis yer whole community

Wid funny folks is packed.

An suppose you ax the question,

Dey’ll one and all declare,

Dat dey nebber got excited on

The Yaller Fever scare.

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

You can view my published works at Bluefish Books: