The Praying Pirate: Sir John Hawkins 1532-1595

c.2005

by

John W. Cowart

An Englishman, Sir John Hawkins, who was a pirate, a slave trader and “a good and charitable man”, saved a French colony near Jacksonville, Florida, in 1565.

While there he also conducted a prayer meeting.

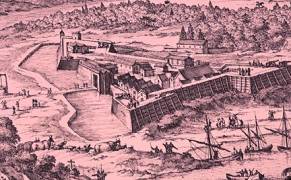

A museum and a palm-log replica of the stockade at Fort Caroline National Monument commemorate the colony; a stained glass window and a pirate ship on the coat of arms at Jacksonville’s St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral commemorate the prayer service.

A museum and a palm-log replica of the stockade at Fort Caroline National Monument commemorate the colony; a stained glass window and a pirate ship on the coat of arms at Jacksonville’s St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral commemorate the prayer service.

Why does a pirate ship – a slaves ship – appear on the church’s emblem?

The story began in Africa:

“I assaulted the town, both by land and sea, and very hardly with fire (their houses being covered with dry palm leaves) obtaining the town, put the inhabitants to flight, where we took two hundred and fifty persons, men, women, and children,” Hawkins wrote in describing a typical slave raid at Cape Verde in 1564.

Hawkins’ own words as well as other contemporary accounts of his voyages are recorded in Richard Hakluyt’s three volume book, The Principal Navagations, Voyages, Traffics , and Discoveries Of The English Nation, which was published in 1598.

Hawkins’ own words as well as other contemporary accounts of his voyages are recorded in Richard Hakluyt’s three volume book, The Principal Navagations, Voyages, Traffics , and Discoveries Of The English Nation, which was published in 1598.

Hawkins had introduced the commercial slave trade to England, thus earning a title for himself. His coat of arms pictured a chained black person, and contemporary descriptions of his voyages paint a horrifying picture of the treatment of human beings.

In his flagship, Jesus of Lubeck, he cruised along the Guinea coast leading a fleet of slavers. His fleet attacked village after village capturing people and stowing them in the cargo holes.

“In the cargo there were over seven hundred men, women, boys and young girls. Not even a waist cloth can be permitted among slaves aboard ship, since clothing even so light would breed disease. To ward off death I ordered that at daylight the Negroes should be taken in squads of twenty and given a salt-bath by the hose pipe… And when they were carried below, trained slaves received them one by one, and laying each creature on his side, packed the next against him, and so on, till, like so many spoons packed away, they fitted onto one another, a living mass,” wrote an officer on the ship.

Hawkins sailed away to the West Indies to sell his cargo, but the wind died and the ship was becalmed in tropic heat for 18 days.

Thirst “put us in such fear that many never thought to have reached the Indies without great death of Negroes and of themselves,” wrote John Sparke, a crewman on Hawkins’ ship. “But the Almighty God, who never suffereth His elect to perish, sent us … the ordinary breeze”.

Hawkins sold the people who survived in Dominica.

Then, knowing it would be more cost-effective to sail home with cargo in the hole than empty, he began attacking merchant ships and stealing their cargos to fill the space the slaves had left. He planned to sell his loot in England.

In those days few governments supported a national navy. Instead, they commissioned individual ship owners called privateers to attach enemy ships. Privateers were respected business men; they paid the government a portion of their take. Pirates operated the same way but without a government’s authorization; they kept all the loot for themselves. They were not respected; in fact, they were often hanged if caught.

To a ship under attack the difference between a privateer and a pirate was not readily discernable.

After numerous adventures looting merchant ships, the Jesus of Lubeck ran low on drinking water, so the fleet sailed north along the east coast of Florida.

French Protestants called Huguenots had established a colony named Fort Caroline at the mouth of the River of May, now known as the St. Johns River. Depending on supply ships from home for provisions, the French had not planted crops.

French Protestants called Huguenots had established a colony named Fort Caroline at the mouth of the River of May, now known as the St. Johns River. Depending on supply ships from home for provisions, the French had not planted crops.

A religious war in France delayed the supply ships.

Starvation stalked the Huguenots.

“We suffered terribly from want, and if I had space I could give you a heart-rending description of our miserable condition. After some of us had already died of hunger, the rest of us were starved until we were nothing but skyn and bones,” wrote Jacques Le Moyne, an artist in the colony.

The colonists stole some food from local Indians.

The Indians objected.

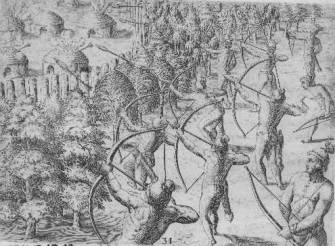

So the French declared war, thinking that their metal body armor would make them invincible against the primitive weapons of the braves.

However, when the Indians saw their arrows bounce off the Frenchmen’s breastplates, they quickly learned to aim for the face. They decimated the French force.

However, when the Indians saw their arrows bounce off the Frenchmen’s breastplates, they quickly learned to aim for the face. They decimated the French force.

The colonists retreated inside their log fort, barred the gate, and soon were reduced to grinding fish bones and acorns to make flour for bread. The Indians camped outside the gate and waited for the trapped Frenchmen to starve.

Finally, Rene Goulaine de Laudonniere, leader of the colony, wrote, “The third of August (Gregorian calendar, 1565) I descrided foure sayles in the sea, as I walked upon a little hill, whereof I was exceeding well apaid (pleased)”.

Hawkins’ ships entered the St. Johns, and Laudonniere notified his men, who “were so glad of those newes, that one would haue thought them to bee out of their wittes to see them laugh and leape for joy.

“Master John Hawkins their Generall came to request of mee that I would suffer them to tale fresh water whereof they stood in great need,” Laudonniere wrote.

Hawkins saw the feeble condition of the French.

“Whereupon being mooued with pitie, he offered to relieue me with 20 barrels of meale, sixe pipes of beanes, one hogsead of salt, and a hundred of waxe to make candels, Moreover forasmuch as he sawe my soldiers goe bare foote, he offered me besides fifty paires of shoes… He did more than this: for particularly he bestowed vpon my selfe a great Jarre (jar) of oyle (oil), a barrel of white Biscuit… wherein doubtlesse he hath wone the reputation of a good and charitable man deseruing to be esteemed as such of us all as if he had saved our liues,” wrote Laudonniere.

The English crewman John Sparke observed a strange thing among the Indians:

“The Floridians… have a kind of herb dried, who, with a cane and an earthen cup in the end, with fire and the dried herbs put together, do suck through the cane the smoke thereof, which smoke satisfieth their hunger”.

Sparke also marveled at the rich abundance of food available in the land:

“The ground yieldeth naturally grapes in great store, for in the time that the Frenchmen were there they made twenty hogsheads of wine. It also yieldeth roots passing good, deer marvelous store, with divers other beasts and fowl serviceable to the use of man… Maze maketh good savoury bread and cakes as fine as flour… The commodities of this land are more than are yet known to any man… it flourisheth with meadow, pasture ground, with woods of cedar and cypress, and other sorts, as better cannot be found in the world… I trust God will reveal the same before it be long to the great profit of them that shall take it in hand”.

While the land and the Indians impressed Sparkes, he did not think much of the Frenchmen, “who would not take the paines so much as to fish in the river before their doores, but would have all things put into their mouthes… Notwithstanding the great want the Frenchmen had, the ground doth yield victuals sufficient, if they would have taken paines to get the same,” he said. “But they, being soldiers, desired to live by the sweat of other men”s brows”.

Yet, despite that feeling, Sparke also felt that God had ordained the meeting of the two groups.

He wrote that the Floridians, as he called the Indians, forced the French to “keepe their fort withal: which they must have been driven into, had not God sent us thither for their succour; for they had not above ten days victual left before we came”.

Laudonniere introduced Hawkins to the Indians as his brother. “Nowe three days passed,” he wrote, “while the English General remained with me, during which time the Indians came in from all parts to see him and asked me whether he were my brother; I told them he was so, and signified vnto them that he was come to see me and ayde me with so great a store of victuals that from thence forward I should haue no neede to take anything of them”.

The “Floridians” raised their siege in the face of superior firepower from the English ships.

Hawkins replenished his water supply and traded one of his ships to the French for some of the cannon from their fort.

Then the two Protestant groups prayed.

Although Hawkins carried no clergymen aboard his ships, he made a practice of leading daily prayers for his men from the 1562 edition of the Book of Common Prayer.

Some details of this first service in America using the Book of Common Prayer were discovered by the late William M. Robinson Jr., former registrar-historigrapher of the Episcopal Diocese of Florida.

Hawkins made another pirate/privateer voyage two years after his visit to Florida. He attacked a ship near San Juan de Ulloa, Mexico, and three of his crewmen were captured by the Spanish and turned over to the Inquisition. Under torture, the pirates confessed to the crime of praying with the Protestant book.

Hawkins made another pirate/privateer voyage two years after his visit to Florida. He attacked a ship near San Juan de Ulloa, Mexico, and three of his crewmen were captured by the Spanish and turned over to the Inquisition. Under torture, the pirates confessed to the crime of praying with the Protestant book.

“As might have been expected the witnesses failed to identify the particular services by their customary prayer book titles; but they could recall only certain verses, responses, prayers, lessons, etc., which oft repeated had impressed themselves on their minds,” Robinson wrote.

“These fragments are readily identifiable as pertaining to particular services…. The Book of Common Prayer was read very much as one finds it in churches today,” he said.

The pirates confessed to using the prayer book both in the prayer service with the French in Florida and in daily services aboard Hawkins’ ships while at sea.

“From thence (Fort Caroline) wee departed the 28th of July (Julian Calendar, 1565) upon our voyage homewards,” Sparke wrote. They met contrary winds and “Wee prolonged our voyage in such a manner that victuals scanted with us, so that we were provoked to call upon Him by fervent prayer, which moved Him to heare us so that we had prosperous wind”.

Only a few weeks after the English left Fort Caroline most of the French colonists were killed by the Spaniard Pedro de Aviles Menendez, who founded, just south of Fort Caroline, St. Augustine, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the United States.

Only a few weeks after the English left Fort Caroline most of the French colonists were killed by the Spaniard Pedro de Aviles Menendez, who founded, just south of Fort Caroline, St. Augustine, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the United States.

Hawkins lived to become the treasurer of Queen Elizabeth’s navy. Once when he quoted scripture to her, Elizabeth swore, “God’s Death! This fool went out a soldier, and has come home a divine”.

In 1588, Hawkins and his cousin, Sir Francis Drake, organized English defenses against the Spanish Armada. Hawkins was killed in 1595 during a sea battle with a Spanish ship off Puerto Rico.

Sir John Hawkins was not the last man whose character mixed religious devotion with a questionable lifestyle – although slavers or outright pirates are rare today. Perhaps he was a hypocrite; perhaps even pirates need to pray. Perhaps he was merely a product of his times when men were sensitive enough to thank God for drinking water and a good wind, but debased enough to steal and enslave other men.

Sir John Hawkins was not the last man whose character mixed religious devotion with a questionable lifestyle – although slavers or outright pirates are rare today. Perhaps he was a hypocrite; perhaps even pirates need to pray. Perhaps he was merely a product of his times when men were sensitive enough to thank God for drinking water and a good wind, but debased enough to steal and enslave other men.

At any rate, Hawkins tried to combine both spiritual and practical elements in his daily life. The standing orders he wrote for his fleet captains on all his many voyages said:

Serve God daily.

Love one another.

Preserve your victuals.

Beware of fire.

& Keep good companie.

This article was published in the Fall issue of Jacksonville Magazine, 1986, under the title Notorious Slave Trader Shared His Food With French Colonists

-------------

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

You can view my published works at Bluefish Books: