c. 2005

by

John W. Cowart

In 1898, just 11 months to the day after the National Bank of Jacksonville opened, it was robbed.

The two thieves, who robbed the forerunner of Barnett Bank Of Jacksonville, made off with one packet of cash containing $5,000, two packets with $1,000 in each, and another packet with $500.

Considering that the bank had been founded with only $43,000 capital, this $7,500 loss was a major setback.

With pistol in hand, bank president William B. Barnett himself hunted the bank robbers for ten days and apprehended a suspect, holding him at gunpoint till police arrived for an arrest.

Such incidents characterize the wild, early days of banking in North Florida.

Indian trading posts, such as Panton, Leslie & Co., served as the area’s banks during the 1700s.

These trading posts gained land from the Indians in exchange for English goods, then traded the land to European settlers.

Since little money circulated, people used tickets, notes, even business and calling cards to pay debts and transact business.

Florida became a U.S. Territory in 1821, and for the next ten years East Florida operated without a bank.

The Bank Of St. Augustine was chartered with $300,000 authorized capital in 1831. This bank maintained a branch in Jacksonville.

Northern interests owned the bank yet its powers were wide. Too wide, many Floridians thought. The institution “had every power except that of killing Indians” complained one contemporary newspaper.

One night, local bank customers tore down the red-and-white-striped pole from the front of a barber shop and set it up at the bank’s front door. “They’ll shave you so close, that you’ll not need being shaved again,” the irate citizens protested.

Such incidents gleaned from several publications such as Dr. J.E. Dovell’s History Of Banking In Florida, papers of the Florida Historical Society, and old newspaper accounts show controversy as an integral part of the area’s banking development.

Anti-bank and anti-statehood feelings gripped northeast Florida. In the 1837 elections East Floridians voted against statehood by a 614 to 255 margin. The West Florida vote to seek statehood carried the day.

Delegates at the state’s 1838 constitutional convention divided into “bank men” (people with money) and “anti-bank men” (people without). One article of the constitution read: “No president, director, cashier, nor officer of any banking company in this state shall be eligible to the office of Governor, Senator, or Representative of the General Assembly”.

The Indian Wars of the 1840s caused Florida to borrow money from banks in Charleston, S.C., and Savannah to finance a $214,000 war effort. Florida was deeply in debt when it became a state in 1845.

The invention of the circular saw in 1850 proved a boon to Jacksonville’s economy. By 1853, the city boasted of 14 saw mills requiring 300 ships to haul away their product each year.

For a time banks flourished – sort of.

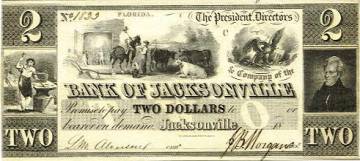

Arthur M. Reed opened a branch of the Bank Of Charleston in a corner of his insurance office, which stood where the Florida Theatre now stands. In 1858 it became the Bank of the St. Johns and issued legal tender such as a $5 note bearing the picture of a railroad steam locomotive or a $10 note picturing a wounded stag.

Reed was a Christian abolitionist and worked his 1,400 plantation home, Mulberry Grove (site of NAS-Jax), with salaried freedmen – not slaves. Yet his bank and his home suffered when the North invaded Jacksonville.

Knowing the thieving ways of Yankee troops, Reed moved his bank to Lake City where, alas, all assets disappeared in the course of the war.

After the war, Reed redeemed his bank’s notes with personal income from his plantation.

The end of the war brought both carpetbaggers and private banks to Jacksonville. Private banks included D.G. Ambler, 1868; Frank Dibble, 1869; Greely & Paine, 1872; and W.B. Barnett & Sons, 1877.

Some of these institutions are ancestors of banks still existing. For instance, Ambler’s private bank became Ambler National Bank in 1874, then the Bank Of The State Of Florida, which in 1903 was absorbed by the Atlantic National Bank, which in turn became First Union National Bank Of Florida, which was acquired by Wachovia.

The end of the war brought the National Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Co., an institution that handled money for former slaves. “Deposits received from 5 Cents upwards” the bank’s adds boasted.

The First National Bank of Jacksonville (not related to the bank of the same name today) was the first national bank in Florida. It was organized in 1874 with a capital of $50,000. By 1885, its resources had grown to $389,973. Shaky phosphate investments led to this bank’s failure on March 14, 1903.

Jacksonville enjoyed her banks and bankers.

An 1886 Board Of Trade report said, “Citizens can point with pride to the substantial and satisfactory condition of banking… The bankers are conservative and have never yielded to the fascination of speculation… Suspensions are conspicuous by reason of their absence, while the defaulting official is an unknown quantity, notwithstanding the tempting proximity of Cuba”.

But Jacksonville banks endured several crises.

Yellow Jack, the personification of yellow fever, rose out of the marshes near Jacksonville during the summer of 1888. The plague depopulated the city, with officials of six banks dying during the epidemic. Every single employee of W.B. Barnett’s bank came down with the fever. Three clerks died.

When Jacksonville recovered from the fever, many area banks invested heavily in the citrus industry. In those days the Orange Belt extended as far north as Fernandina.

In a single night most of that Orange Belt died. On February 7, 1895, temperatures in Florida fell to 11 degrees and stayed there for a week. Snow fell as far south as Tampa. Citrus trees cracked. Estimated loss to the state -- $75 million.

Six years later, Jacksonville banks thawed out.

On May 3, 1901, the city – including most bank buildings – burned to the ground.

But a May 7th newspaper announced, “The vault of the Commercial Bank was opened by its combination yesterday and not a paper was seen scorched”.

Similar announcements followed for five other city banks – buildings destroyed, money and papers saved. They did business at temporary locations.

Barnett, with the only undamaged bank building in the city, shared its facilities with competitors in a cooperative endeavor to get Jacksonville on its feet again.

Jacksonville’s banking community once again not only survived but progressed both financially and technologically as new bank buildings sprang up to replace those destroyed in the fire.

Yes, Jacksonville banks have always been in the forefront when it comes to bringing new technology into the city. During its first 11 years of existence the Barnett Bank introduced Jacksonville’s business community to the telephone (the bank’s phone number was 37), to the typewriter, the bicycle, the fountain pen, the loose leaf binder, and, of course, the Burroughs Adding Machine..

A front page story in the January 14, 1898 Florida Times-Union & Citizen newspaper reflects the technological progress always evident in Jacksonville banking:

A front page story in the January 14, 1898 Florida Times-Union & Citizen newspaper reflects the technological progress always evident in Jacksonville banking:

“The First National Bank Of Florida has placed a unique pencil-sharpener in the bank lobby for the benefit of the public. All that is necessary is to stick the point of the pencil in the machine, turn the crank, and a perfect point is the result. All who have pencils to sharpen are invited to try it”.

What will they think of next?

===================================

About 1945 at the C.I. Capps Foundry, Jacksonville, my father, Zade M. Cowart, who was a master molder, cast dozens of these bronze grills. Branches of the Florida National Bank used these ornamental screens around the teller cages instead of the traditional iron bars.

More photos of early Florida currency can be found at Uncle Davy’s Americana http://www.collectorsnet.com/uncledv/index.htm

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

You can view my published works at Bluefish Books: