c.2005

by

John W. Cowart

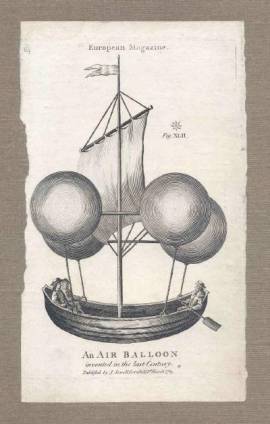

On January 28, 1878, a strange apparition floated in the air above Jacksonville.

Laborers stopped pushing and pulling the giant saws in the city's lumber mills. Crews jumped off the ships tied up to the docks along Bay Street and craned their necks backward to look up.

Business halted as customers ran out of stores and clerks deserted the counters.

People ran out of their homes. Children cringed clinging to their mother's aprons.

Everyone crowded into the streets and pointed at the sky.

The next day, the Sun and Press newspaper reported, "A large balloon containing one man is reported to have passed over this city yesterday afternoon about 5 o'clock. It appeared to be about a mile up, and was going in a southeasterly direction".

Thus began Jacksonville's aviation history.

The unknown balloonist was the first person to fly over the city but hundreds of Jacksonville flyers have followed his lead.

When the Seventh Annual State Fair was held here on February 23, 1882, Professor T. F. Burton "soared skyward amid gasps of mingled fear and delight," said the Daily Florida Times, the newspaper of the day.

The aeronaut (as flyers were called in those days) hung from a trapeze suspended beneath a hot air balloon. When a breeze pushed the balloon toward the St. Johns River, the Aeronaut slid down a guy-rope some 20 feet to safety. "The professor stuck in the mud at the upheaval and the airship collapsed into the river."

The aeronaut (as flyers were called in those days) hung from a trapeze suspended beneath a hot air balloon. When a breeze pushed the balloon toward the St. Johns River, the Aeronaut slid down a guy-rope some 20 feet to safety. "The professor stuck in the mud at the upheaval and the airship collapsed into the river."

In 1905, another type of balloon, "The Wonderful California Airship" rowed its way across the Jacksonville skyline powered by a young man named Foilette.

"It does not depend on a motor but is propelled and steered with oars. Mr. Follette rows it exactly the same way as he would a boat; according to the stroke he gives the machine will go to right or left, forward of backward, up or down, and ballast is only carried in anticipation of an emergency," said the December 17 Florida Times-Union.

This gentleman posed for his picture over the city skyline in a biplane

sporting a Jacksonville pennant.

Technology marched on abandoning the oar-powered balloon.

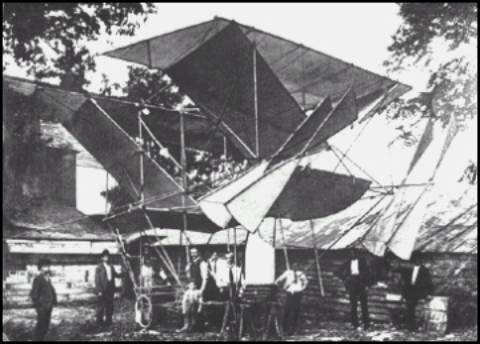

The next year saw a double-winged kite with a man sandwiched between the wings fly over Jacksonville Beach. Two steam-powered motorcars racing side by side pulled the kite into the air.

Israel Ludlow, an attorney, invented this flying device. On Easter Sunday, 1906, he demonstrated it.

Here's how a reporter recorded the event:

"Promptly at 3 o'clock Ludlow attached the guy ropes to the big kite and the crowd, attracted by the announcement of the intended flight, lined itself along the Hotel Continental pier and along the beach. In front of the kite the little rudder flapped back and forth, back and forth, in the strong south wind...

"Every one realized that Ludlow, calmly working his way through the wires and bamboo supports to his seat in the center, was taking his life in his hands.

Israel Ludlow's craft crashed paralyzing him.

.

"Two White Steamers wheeled in to position and the guy ropes were made fast to them...Then the cars were crowded with spectators to add weight.

"The cars, jumping at once in their high speed, took up the slack in the tow. There was a sudden jerk, a whirl of dust and sand, and the kite was off.

"Up into the air it shot as though it was some mighty projectile hurled from the iron jaws of a giant cannon. It did not pitch, did not waver, did not tilt...

"Up and up went the kite, going ever higher and higher. Ludlow pulled on the rudder-ropes to swing it more directly into the wind..."

But as the crowd began to applaud, Ludlow's kite began to come apart.

"The drivers halted the cars with a jerk that almost unseated some of the passengers.

"A shattered piece of bamboo, like a premonition of what was to come, came free of the wires and hurtled down through the air. The front half of the kite lifted quickly under the high pressure of the wind. Straight up in the air it went. There it quivered for just an instant; made one mighty effort to tear itself free; failed; bent backward; and broke again.

"Crackling and splintering every instant it crashed through the top of the remaining half and jammed itself down over Ludlow..."

The driver of one car, "half frantic because he could not help the man alone up there in the air, ran back toward the kite, now falling like some great stone, its lifting power gone; all crippled, shattered and helpless...

"Crashing downward through space for more than one hundred and fifty feet; pinned helplessly to his seat by the big wings of the aeroplane that was rushing its inventor to what seemed certain, instant death; beyond all reach of human aid; powerless and utterly helpless in the hands of heartless, unpitying Fate"..., Israel Ludlow hit the sand.

The impact paralyzed Ludlow and the accident shook the community; but Jacksonville refused to give up flight.

Aviation experiments continued here.

The first motor-powered airship ever to fly in Florida took off from Southside at 5:10 p.m. on February 3, 1908. Thousands of citizens watched native son Lincoln J. Beachey fly a cigar-shaped gas-filled bag equipped with a four-cylinder motor.

"The great propeller... like some monster double paddle of the Indians of old, whirled the sand in all directions... Beachey cast off his anchor and the ship as easily, lightly, gracefully as some great feathered bird, shot up into the heavens, outlining itself against the sunset colors of the early evening and the cool, gray background of the sky," the Times-Union reported.

The airship ascended 200 feet, cruised over the Dyal-Upchurch Building at Main and Bay streets, then returned to Southside. It came down to 35 feet and Beachey threw out the anchor.

"Easily as the merest of birds drops to the swinging topmost bough of some favored tree, the Beachey airship settled," the newspaper said.

Beachey's flight lasted 12 minutes.

1910 was a big year for flight in Jacksonville. "Dainty Dot LeRoy, the world's most famous woman aeronaut" ascended in a balloon at the Florida Ostrich Farm.

"She has no fear of the monster gas bag above her head and declairs that she never thinks of what might happen if the balloon acted cranky in mid air," the Times-Union reported.

The balloon did get cranky.

Our first female flyer landed in the river and had to be rescued by a launch. Around the turn of the century, the river seems to have hosted as many balloons as boats.

Also in 1910, on May 21, at Moncrief Spring Park, Charles K. Hamilton, known as “The Daredevil of the Air”, raced his Curtis biplane, the first heaver-than-air flying machine seen in Jacksonville, against a Cadillac driven by Dexter Kelly. The biplane soared to the height of 2,500 feet and reached a speed of 60 miles per hour in a dive, yet the automobile won the five mile race.

Hamilton's plane in Phoenix, Arizona

But what was to have been 1910's biggest aerial event was the Christmas Day Moncrief Park Aviation Demonstration sponsored by the Florida Times-Union.

For weeks ahead the newspaper ran promotional articles and half-page ads with photographs of flying machines. Headlines proclaimed BIRD-MEN WILL INVADE JACKSONVILLE -- SKY PILOTS AWAIT SIGNAL TO FLY CHRISTMAS DAY -- TIMES-UNION GREAT AVIATION MEET: GET IN THE HABIT OF LOOKING UP.

News articles touted "The most sensational exhibition ever pulled off in any Southern city."

The paper arranged for railroads to bring spectators to the city at reduced fares. Pinkerton guards were hired.

"Important among the features of the aeroplane tournament on Christmas day is the appearance of the Curtis aeroplane which has taken the lead in advancing the science of aviation along practical lines during the past year," one paper said. "First in cross country flights from city to city, first to be used in bomb dropping experiments: first used for demonstrations of aerial sharp shooting by an officer of the United States Army: first to fly from the decks of a United States cruiser, and possibly most important of all, the first aeroplane from which a wireless message was ever sent while the machine was in flight".

All the hoopla was before the meet.

On December 26, the EVENING METROPOLIS, the city's other newspaper, carried a small announcement:

"Both aeroplanes broken and flights abandoned early."

One of the machines broke a propeller after circling the race track twice. The other plane cracked a cylinder after circling three times.

"The meet was abandoned with the three flights. Some 2,000 people were disappointed but the accidents could not be helped," the Metropolis said.

But set-backs did not stop aviation in Jacksonville.

In February 1913, Robert G. Fowler created a sensation by landing at Pablo Beach after flying cross-country from Long Beach, California. He was the first to fly across the continent from west to east.

Fowler had left California the previous October!

In 1916, Earle Dodge opened a flying school at a site that is now NAS-JAX. He taught flyers in Curtis Hydro-aeroplanes there till the army took over the site in 1917 and military pilots began training there.

Another long-distance flyer, then Lieutenant James H. Doolittle -- later famous for leading the World War II raid on Japan -- made his name in Jacksonville. On September 4, 1922, he took off from Jacksonville Beach and flew his DeHaviland to California in world record time of 21 hours and 18 minutes.

Another long-distance flyer, then Lieutenant James H. Doolittle -- later famous for leading the World War II raid on Japan -- made his name in Jacksonville. On September 4, 1922, he took off from Jacksonville Beach and flew his DeHaviland to California in world record time of 21 hours and 18 minutes.

Robert Kloeppel Sr., later the owner of Jacksonville's George Washington Hotel, had built his own heavier-than-air machine in 1910. He tested it on East 14 Street in Springfield. It flew it a distance of 75 feet in two minutes at a height of four feet.

Then it crashed, a total wreck.

Kloeppel never tried to fly again but he always remained active in the Aero Club of Jacksonville. He offered a $1,000 reward to the first person to fly across the Atlantic.

Charles Lindbergh flew to Paris in 1927.

He returned to this country aboard a warship, the USS Memphis. While the ship was still 75 miles out to sea, Jacksonville aviator, Laurie Yonge flew his own Waco biplane over the Memphis and dropped a note to the deck inviting "The Lone Eagle" to Jacksonville.

He returned to this country aboard a warship, the USS Memphis. While the ship was still 75 miles out to sea, Jacksonville aviator, Laurie Yonge flew his own Waco biplane over the Memphis and dropped a note to the deck inviting "The Lone Eagle" to Jacksonville.

Lindbergh accepted.

A parade in October welcomed the World's Most Famous Man to Jacksonville.

The day he flew in, schools let out and everyone took the day off.

Headlines proclaimed: THOUSANDS BRAVE RAIN TO WELCOME LINDBERGH.

Just as Lindbergh landed at the Jacksonville Municipal Airport, a heavy downpour, 2.23 inches, fell.

In spite of the rain, 150,000 people stood cheering on Jacksonville streets to see Lindbergh ride through downtown in an open car.

"I don't remember any rain," said Mary H. Mortellaro, 72, who as a 12-year-old attended the parade. "Probably as a kid, it didn't bother me.

"I remember Aunt Laura took me and DeeDee down to see him. There were huge crowds but she bustled us right up to the front were we could see.

"He rode by Jacobs Jewelers in a big old touring car. The top was down and he sat up on the back waving to people.

"He was curly headed and tall and lanky -- looked just like an ordinary man -- just like his picture in the paper. We were thrilled," she said.

In the George Washington Hotel ballroom, Kloeppel presented Lindbergh with a $1,000 check.

Jacksonville's Laurie Yonge once set the world's endurance flying record for small planes by staying aloft over Jacksonville Beach for 25 hours. The previous record had been only 13 hours.

When Yonge landed his plane, "The Spirit Of Jacksonville", he was congratulated by city commissioner Thomas C. Imeson.

Yonge organized Florida's first Civil Air Patrol squadron and the first aerial ambulance service in Jacksonville.

Under Imeson's supervision that the city built our first municipal airport which was named for him posthumously.

Clint Frank began his aviation career at Imeson Airport.

Frank has the distinction of having served for 35 years in Jacksonville for Eastern Airlines. He retired earlier this year as manager of passenger and cargo sales.

"For one manager to stay in one city all that time is unusual," he said. "But I'm glad I was able to do it. Other people work all their lives to be able to come to Florida; but here I am."

When Frank joined Eastern in 1951, only one travel agency existed in the city. "Now there are about 70 I would say; and the increase in service for air travelers has done it," he said.

The lone agency in 1951 sold only 5 percent of the seats on planes flying from Jacksonville; the airlines handled all the other bookings. Now 75 percent of all bookings are handled by travel agents, he said,

"I remember that in the early '50s what stands out in my mind was that Eastern had 60 plus flights a day into Jacksonville -- DC3s, Constellations, DC4s. Jacksonville was a small hub for piston engined aircraft to stop for fuel.

"When the jet era came in the mid '60s, Jacksonville was not needed for refueling. Flights could go directly to their destinations.

"We lost in number of flights, but there was no loss in service because jets were so much quicker. Therefore the total number of seats kept going up," Frank said.

Frank helped in aviation's transition from Imeson to Jacksonville International Airport.

"The old airport was antiquated and larger planes needed a better facility. Lew Ritter who was mayor then was criticized a lot for the new airport but if he had not stuck to his guns and done it, we'd be in bad shape now. It cost about $28 million when it was built, but if you had to do it today, think what it would cost."

Frank missed seeing the landing of the British Airways supersonic Concorde jet on May 14. The Concorde, world's fastest airliner, had come from London to Jacksonville at 1,340 miles per hour and at an altitude of 60,000 feet.

"The generation of aircraft we have now will be with us for a long time," Frank said. "The Concorde is supersonic but it's also super expensive and super costly to operate. That's why they haven't built any more of them. I think it will be another ten years before we seen any more major changes in aircraft technology.

"But I may be wrong about that; I still find it hard to believe that airplanes can actually fly," he said.

-----

Such were the early days of flight in Jacksonville.

How far have Jacksonville's contributions to aviation gone?

Well, before his death in 1979, my father, Zade Maxwell Cowart Jr., a Jacksonville native and a master molder, worked at NAS-JAX.

There he crafted parts for some of NASA's 1971 Lunar Rover equipment, the golf-cart like vehicle astronauts used to drive around on the moon’s surface and abandoned when they left.

Yes, astronauts took my Daddy’s work from Jacksonville to the moon.

It's still up there.

Lunar Rover (far right) was abandoned on the surface of the moon

This article appeared in the September, 1987, issue of Jacksonville Magazine.

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at