DUVAL COUNTY MEDICAL SOCIETY HISTORY

c.2005

by

John W. Cowart

Late one August afternoon in 1854, doctors of the Duval County Medical Society (DCMS) helped trundle a cannon to a wharf along Bay Street.

They aimed it across the river and waited for their target.

An epidemic of yellow fever was sweeping through Savannah, Ga., and the doctors were upset because Nick King, captain of the steamship Welaka refused to observe a quarantine.

King carried the U.S. mail from Savannah to Palatka and he felt his ship ought to be exempt.

The doctors showed him it wasn’t. They felt Jacksonville’s health was more important said medical historian D. Webster Merritt, author of Hundredth Birthday, Duval County Medical Society, 1853-1953.

Although King kept his ship close to the south bank of the St. Johns, the doctors used handspikes to elevate the muzzle and fired two 32-pound cannonballs into the ship’s cabin. “It was not exactly a legal way of enforcing quarantine but it proved very effectual,” said the January 25, 1876, Tri-Weekly Union newspaper.

Today, the only shots most DCMS members are likely to hear in the course of their duties is the starting gun at high school athletic events; DCMS doctors volunteer their services at some high school events to help injured players. For the past 15 years the DCMS has provided free pre-participation health examinations for Jacksonville junior and senior high school athletes and cheerleaders.

The DCMS is 133 years old, the oldest medical society in the state.

It was founded on May 25, 1853, by local physicians meeting in the office of Dr. William J. L’Engle,

It was founded on May 25, 1853, by local physicians meeting in the office of Dr. William J. L’Engle,

Dr. A.S. Baldwin was the founder, but Dr. John S. Murdock was elected first president.

Charles Dickens Jr., son of the famous author, visited Jacksonville in 1855 and met “one of Jacksonville’s most eminent physicians” on the street.

Dickens said, “He was a little dark man with spectacles on his nose, and a quick nervous step indicative of the enquiring and active mind within him… (The city) brings him as many patients at five dollars a visit as he cares to have. For by a merciful dispensation of Providence, there comes a time annually to almost every resident in Florida when the conviction comes that he has a liver, and that that liver is out of order…”

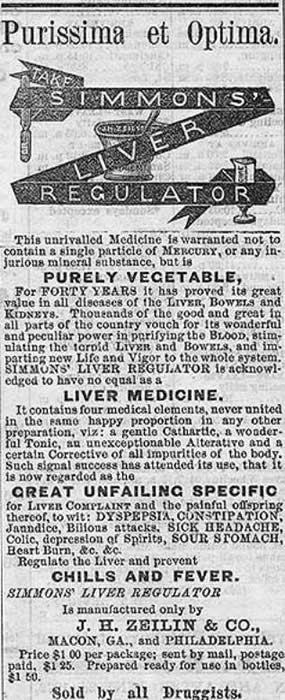

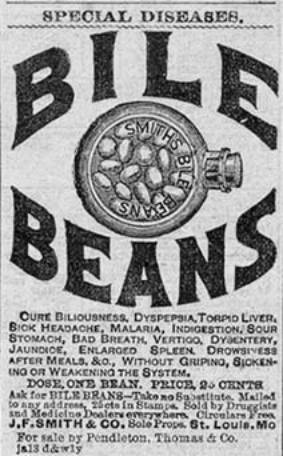

Dickens observed that posters advertising cures for liver complaint were posted on nearly every pine or cypress tree within sight of the St. Johns.

Ads in 19th Century newspapers support Dickens’ observations about Jacksonville’s concern for health:

A family provided with a comprehensive household specific like HOSTETTER’S STOMACH BITTERS is possessed of a medicinal resource adequate to most emergencies…

Of all the preparations brought to public notice, none deserves greater commendation than HOME STOMACH BITTERS, being extracted from the best vegetable materials…

To all who are suffering from the errors and indiscretions of youth, nervous weakness, early decay and loss of manhood, I will send a receipt that will cure you… This great remedy was discovered by a missionary in South America. Send a self-addressed envelope to…. (I wonder if that’s the same company that keeps sending me all that e-mail about my manhood?)

In 1877, Miss Caroline Singleton wrote this testimonial:

“I was bitten on the breast by a snake about two months ago and was attended by Dr. King, who failed to do me any good. I then called on the Indians Doctress and Fortune-teller at 37 Newnan Street and was cured by her in four weeks”.

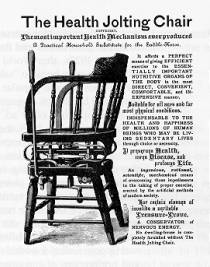

Also advertised was a HEALTH JOLTING CHAIR, a seat mounted on powerful springs which were tightened by cranks, levers and pulleys. The patient would wind it up, sit on it, then release the springs – the ad said it was a sure cure for everything from bad complexion to constipation.

Also advertised was a HEALTH JOLTING CHAIR, a seat mounted on powerful springs which were tightened by cranks, levers and pulleys. The patient would wind it up, sit on it, then release the springs – the ad said it was a sure cure for everything from bad complexion to constipation.

In spite of intense competition form home cures, jolting chairs and quacks, Jacksonville doctors continued to serve the community.

Since many people lived on farms in outlying areas it was common for doctors to travel by canoe or on horseback to reach their patients.

William F. Hawley, who survived the great Jacksonville yellow fever epidemic of 1888, said, “I well remember old Dr. Beatty who drove over the countryside in a little two-wheel cart drawn by a little black mare; they all seemed part of each other.

“Every drug store had a leech jar from which a worm could be secured to suck the blood from bruises, black eyes and for reduction of blood pressure. The blood sucking worm when full of blood could be stripped of his internal load and put back to work again,” he said.

Most doctors in those days compounded their own prescriptions and one of the most popular was a draught called Blue Mass. “The nastier the taste, the better the effect” was the slogan, Hawley said.

When Hawley was a boy he fell into the river and caught a cold which put him to bed for months. His family told the doctor of his decline.

“He punched me in the ribs and I let out a yell, whereupon the old doctor said, ‘Decline nothing! Give the little devil some Blue Mass’,” Hawley said.

But Jacksonville doctors were not limited to prescribing Blue Mass as an August 13, 1874 , baseball game proved. The Tri Weekly Union reported:

“Two of the members… began quarreling with each other. Finally (Mannie) Franklyn, after saying something to (Archie) Terry, took his position as catcher behind the bat. Terry followed him up and calling him a d-n s-n of a b---h, struck him a horrible blow across the temple with a bat, crushing his skull and knocking him senseless. He was then taken home in a dying condition…

“When physicians, Drs. J.D. and F.A. Mitchell, were called, he was in strong convulsions, moaning and gasping, and from all appearances, about to die. It was thought best to trephine the skull, which was immediately done, several pieces of bone being removed, and the clotted blood which had collected to a considerable extent was cleaned away. Then, by raising a large piece of the skull that had been forced down upon the brain, the patient was given almost immediate relief…”

Two pioneer doctors of the DCMS were Dr. Abel Seymore Baldwin and Dr. Francis W. Wellford.

Baldwin was the only physician in a 20-mile radius when he came to Jacksonville in 1838. He was a founder of the DCMS and was later first president of the Florida Medical Society in 1874. He helped bring railroads to Jacksonville and his scientific studies of tides led to the construction of the jetties at the mouth of the St. Johns which made it possible for the development of Jacksonville as a major port.

Dr. Wellford earned distinction by volunteering to serve inside Fernandina’s quarantine area during the yellow fever epidemic of 1877. From inside the stricken city, Wellford, who was a former DCMS president, wrote to his friend Dr. Richard D. Daniel, who was then president:

“I am tired after more than 50 visits today, yet I am hearty and well and on the principal of naught being in danger, I am brighter and brisker than half the people here. Don’t think I am either reckless of boastful, I appreciate life as most, but thank God I appreciate something higher still than mere physical existence. When you kneel down and night to offer thanks for present favors and future good, ask for me that God bless that immortal soul that will survive the grave. And if your prayers be granted, I care not how soon the summons may come”.

Dr. Wellford caught yellow fever and died less than a week after he wrote that letter.

The headquarters building of the DCMS, at 555 Bishop Gate, which was dedicated on March 3, 1986, is named the Baldwin-Wellford Building in memory of these two doctors.

During the Civil War most Jacksonville doctors served with Confederate forces. One served with the damnyankees. While the physicians were in the service, the records of the DCMS were buried for safekeeping, but after the war when they were dug up, the doctors found water had seeped into the containers destroying most of their earliest papers.

After the Civil War, Jacksonville became the nation’s primary health resort. Between 1865 and 1872 the resident population increased from 2,000 to 7,000 and over 30,000 guests annually registered at Jacksonville hotels during the winter months.

“The chief attraction for Northern people to go to Jacksonville… is so great that if the whole population of the town should turn out, their houses would not furnish room for the army of consumptives who have found their way there,” said the pamphlet Going South For The Winter With Hints For Consumptives by Dr. Robert F. Speir in 1873.

Another pamphlet, Petals Plucked From Sunny Climes by Silvia Sunshine in 1885 said, “Too many invalids, before coming to Florida, wait until they have already felt the downy flappings from the wings of the unrelenting destroyer, and heard the voices from a  spirit-land calling them, but come too late to be benefited and take a new lease on life. The climate should not be blamed because the sick will stay away until death claims them…”

spirit-land calling them, but come too late to be benefited and take a new lease on life. The climate should not be blamed because the sick will stay away until death claims them…”

Many sick people who came to Jacksonville for their health died here. Some had spent all their money to get here and died in hotel outhouses or in the streets.

To care for such indigent patients, Mrs. Theodore Hartridge, Mrs. J.D. Mitchell, whose husbands were physicians, and Mrs. Aristides Doggett , whose husband was a lawyer, founded St. Luke’s Hospital on March 11, 1873. St. Luke’s Hospital opened in a two-room frame building with beds for four patients.

At 3 a.m. on July 22, 1876, a new St. Luke’s building at Market and Ashley streets was set on fire by vandals just a few days before it was to open.

Two years later, and even better facility at Palmetto and Duval streets opened. In 1882, Dr Malvina Reichard, a pioneer woman physician, became St. Luke’s first resident physician at a salary of $523.50 a year.

In 1885, St. Luke’s instituted a training school for nurses, the first permanent on in Florida. Hospital instructions included the rule: All Patients Must Be Bathed Once A Week.

The Battleship Maine exploded in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898; the Spanish American War began.

Over 30,000 U.S. troops were staged in Jacksonville for the invasion of Cuba. They camped in Springfield Park at Camp Cuba Libre. Many died there.

Typhoid fever swept the camp.

DCMS members and army doctors fought the disease.

“Almost as many men died of typhoid in Jacksonville as were killed in combat and more were hospitalized in the city on a single day during the peak of the epidemic than the 1,662 who were wounded in action overseas during the entire Spanish-American War,” said Richard A. Martin, author of St. Luke’s Hospital: A Century Of Service, 1873-1973.

It was not until 1910, when DCMS member Dr. Charles E. Terry was City Health Officer, that typhoid was beaten in Jacksonville. Terry influenced legislation demanding that outdoor toilets be screened from flys and the number of typhoid cases dropped from 110 to 5 within six months.

The DCMS again lost its early records in the Jacksonville fire of 1901. But the day after the fire, members helped attend fire victims in a field hospital set up in what is now Hemming Plaza.

In 1918, an 89-car train arrived in Jacksonville bringing the Ringling Brothers Circus. The show did not go on. The world-wide influenza epidemic got to town first. By October 10th, one out of every three people in Jacksonville were down with the flu.

A Times-Union editorial even advised, “Kissing should be foregone during the period of illness”.

Stores, bars and movie theatres closed. People walking the streets wore face masks. 95 of the telephone company’s 191 operators were sick and phone service faltered.

On October 12, one thousand, two hundred sixty seven new cases were reported and 21 people died.

That same day the Jacksonville Ministerial Alliance announced that all houses of worship would be closed for the duration of the epidemic. But the churches did open soup kitchens and emergency hospitals were set up at the City Prison Farm, YMCA and at the old Stanton High School.

Between September and November, 17,000 cases of influenza were officially recorded. Dr. W.W. MacDonell, City Health Officer, estimated, “Nearly 30,000 persons were infected with the disease”. There were 1,051 deaths among Jacksonville civilians and 155 among soldiers stationed at Camp Johnson (now NAS-JAX).

Jacksonville doctors coped.

“From its establishment in 1853 until the present, the members of the Duval County Medical Society have strived to improve the quality of life in the community as the professionals in the field of medicine. Through determined persistence and a willingness to meet change, this professional association has a proven record of participation in health and community activities,” said Carolyn Kirkland-Webb, managing editor of Jacksonville Medicine, the bulletin of the DCMS.

Dr. Benjamin Chapman joined the DCMS in 1920. At first he could not afford a car so he rented a horse for 50 cents a day to make housecalls.

In a 1980 newspaper interview when he was 95 years old, Dr. Chapman said, “Patients were poor. They would say, ‘Doctor, I haven’t got any money to pay, but I’ll give you a piece of ham and a half-dozen eggs now, and I’ll pay you later’. The people were always pretty good about paying you later”.

When Dr. Chapman bought his first car, a Maxwell, he ran out of gas on his way to his first housecall. “When I bought the car, nobody told me I had to buy gas too,” he said.

Dr. Kenneth Morris joined the DCMS in 1927. In a 1978 interview he told of surgery in the 1920s:

“The anesthetic would not relax the patient very well, so they would be breathing fast and moving most of the time on the operating table. In those days you had to be sort of a wingshot to catch an artery because the patient was breathing so hard”.

He said, “Office visits usually ran about $3 to $5. Operations cost between $100 and $150 and you could get a hospital room for as little as $7 a night”.

During the Depression it cost $15 to deliver a baby in a local hospital and one dollar for home delivery. Some people could not even afford that.

One doctor delivered a son to a family in a deserted boxcar on the railroad tracks near Talleyrand Avenue. There was no water, light or heat. A 16-year-old secretary from his office helped him because he himself could not afford a nurse. He did not charge the family.

“Everyone who goes into medicine initially does so out of a sense of wanting to help people and alleviate pain and suffering,” said Dr. Clyde M. Collins, unofficial DCMS historian. “But involvement in our materialistic society lures them – plus the need to pay the rent, pay the nurse, buy the car, join the country club and all that – They sometimes forget why they started.

“But the original dedication in there. And humanitarian dedication, such as the stories told of old-time doctors they tell about, will be the one thing to bring medicine out of the doldrums”.

The DCMS seeks to inspire and nurture that spirit of dedication in its 1,100 members and to meet the modern problems and challenges of Jacksonville doctors.

Today, the DCMS sponsors the examinations for student athletes, a Peer Review Committee, a physician referral service, the “Health Line” column in the Jacksonville Journal, the “To Your Health” weekly television program, and the “Ask The Doctor” radio program.

“Duval County physicians work hand in hand with hospitals and other health professionals to meet the health care needs of both the individual and the community. This concern for others is the cornerstone on which the Duval County Medical Society was founded,” said Mrs. Kirkland-Webb.

Dr. Charles P. Hayes Jr., president of the DCMS, said, “The challenges to the medical profession during the past few years are serious and important, not only to physicians but also to the public: professional liability crisis, hospital-physician relations, alternative delivery systems, encroachment upon medical practice by allied health professions, the federal government’s withdrawal from its commitment to health care for the elderly.

“In 1986, we plan to go forward with the things that seem to work, abandon those that don’t, and be ever alert for the new and innovative,” he said.

This article was published in the Fall, 1986, issue of Jacksonville Magazine.

END

Thank you for visiting www.cowart.info

I welcome your comments at John’s Blog!

You can E-mail me at cowart.johnw@gmail.com

Return to John’s Home Page

You can view my published works at